USPTO After Final Petition Statistics – Are Things as Bad as They Appear? (Part VI)

Originally published on IPWatchdog

Julie Burke, Ph.D.

Michael Spector

While researching the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s (USPTO) treatment of final Office actions for previous articles (Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV and Part V), we noticed USPTO petition pendency and grant rate statistics often differed from results of our analysis. Applicants relying on the pendency information provided by the USPTO Data Visualization Center prior to January 2021 would expect their petitions filed after final to be decided on average in two to three months. However, our prior publications document decisions often inexplicably delayed to such an extent that applicants were compelled to take other action to avoid abandonment of their applications. The USPTO has updated its after final petition data twice since the publication of Part V – now showing a 12-month rolling average processing time of greater than 180 days. A six month delay in processing such petitions renders any resulting decision as futile. Here, we investigate petitions decided during the fourth quarter of 2020 to determine why petition pendency has skyrocketed and what this means for applicants seeking to challenge an Examiner’s premature determination of finality.

USPTO After Final Petition Process Delays Affect Petition Outcome

As noted in Part IV, final Office actions close prosecution with a six-month deadline. Should after final practice fail to place the application in condition for allowance, applicants must file a Notice of Appeal, a Request for Continued Examination (RCE) or let the case go abandoned. When an applicant files a RCE, the USPTO then uses that RCE to justify dismissing the petition as moot on the basis that the applicant withdrew finality via the RCE. The effort and fees associated with filing a forced RCE, coupled with the inevitable dismissal as moot, may dissuade practitioners from challenging future premature final Office actions via petition.

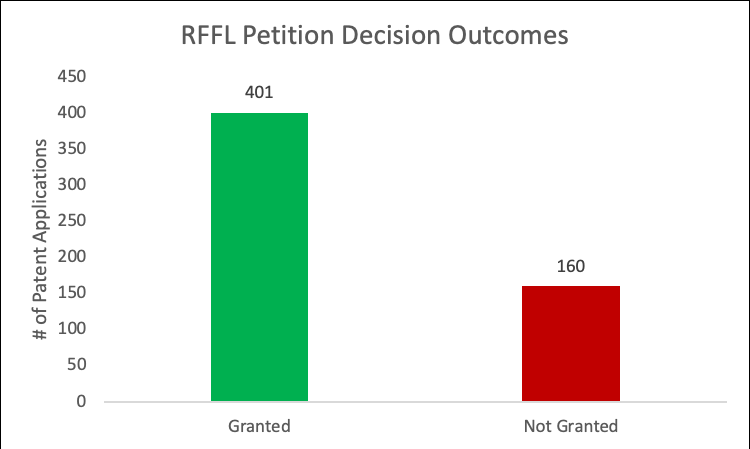

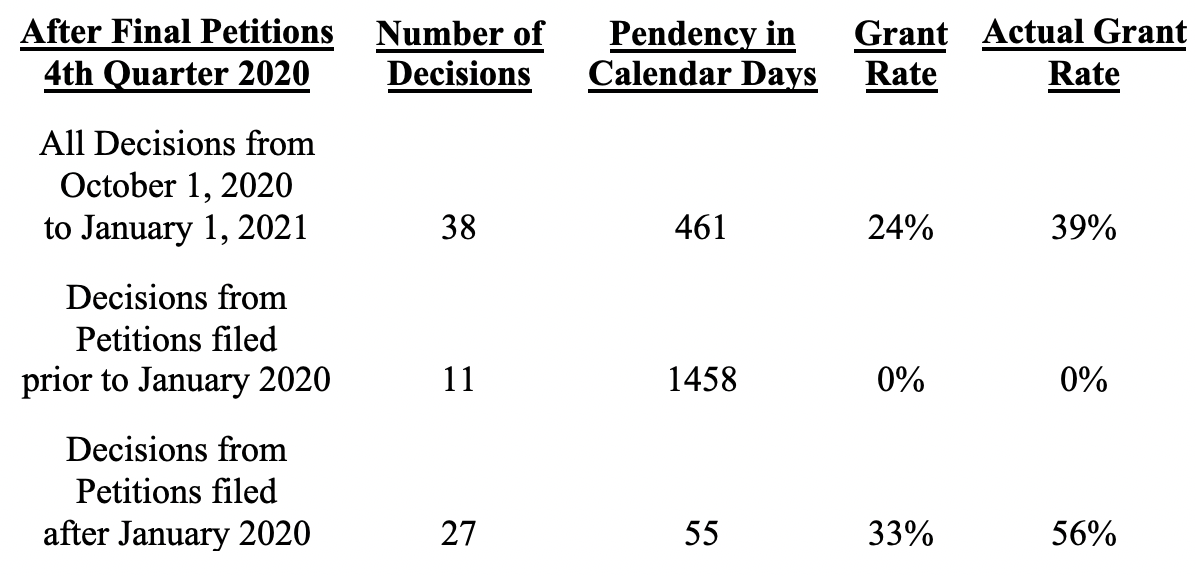

If an applicant seeks to challenge an improper final Office action, filing such a petition does not stop the six-month clock. While applicants are subject to a two-month petition deadline, the USPTO can use its discretion to decide the petition quickly or slowly. We have found that lengthy delays in deciding petitions, or even in entering petitions into PAIR Transaction History, are commonplace. Part IV. Yet, frustrated applicants can only wait four months for a decision, if the request is filed close to the sixty-day deadline. USPTO personnel routinely warn petitioners to expect a three to six month wait for petition decisions. As a result, many applicants choose not to file a petition to reverse a premature final action. Table 1 includes pendency data and grant rates for petitions related to premature final rejection, obtained from the USPTO Data Visualization Center.

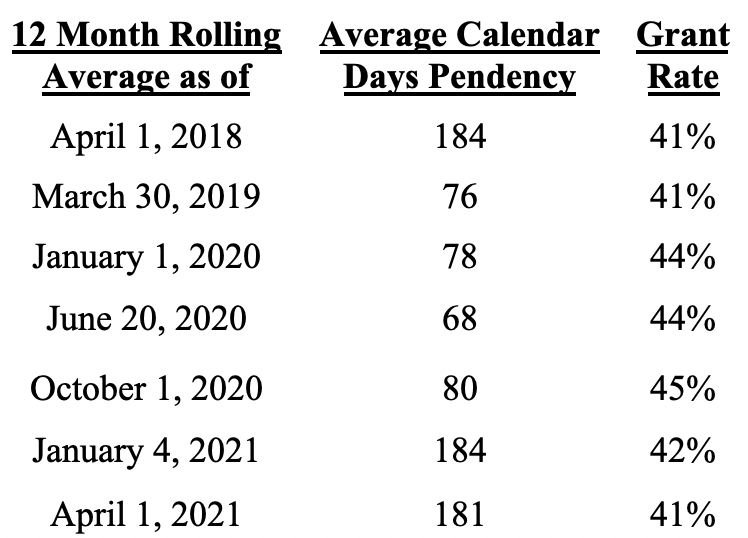

Table 1

As noted, lengthy petition processing delays are especially perilous after final. In the 12 months prior to April 1, 2018, petitions relating to premature finality were decided in an average of 184 days, or, six months. Between March 2019 and October 2020, the USPTO significantly improved its processing procedures and addressed petitions relating to premature final rejections in an average of 68-80 days, or two to three months. Since 37 CFR 1.181(f) requires such petitions to be filed within two months of the final Office action, the further two to three months wait ensures most petitioners would receive a decision on the merits of their petition in advance of their six month statutory response time. However, beginning January 4, 2021, the 12-month rolling average of USPTO pendency rates jumped 130%, to over 180 average days, or six months, seemingly making the filing of a petition to challenge an improper final Office action fruitless.

Why Did the After Final Petition Pendency Skyrocket 130%?

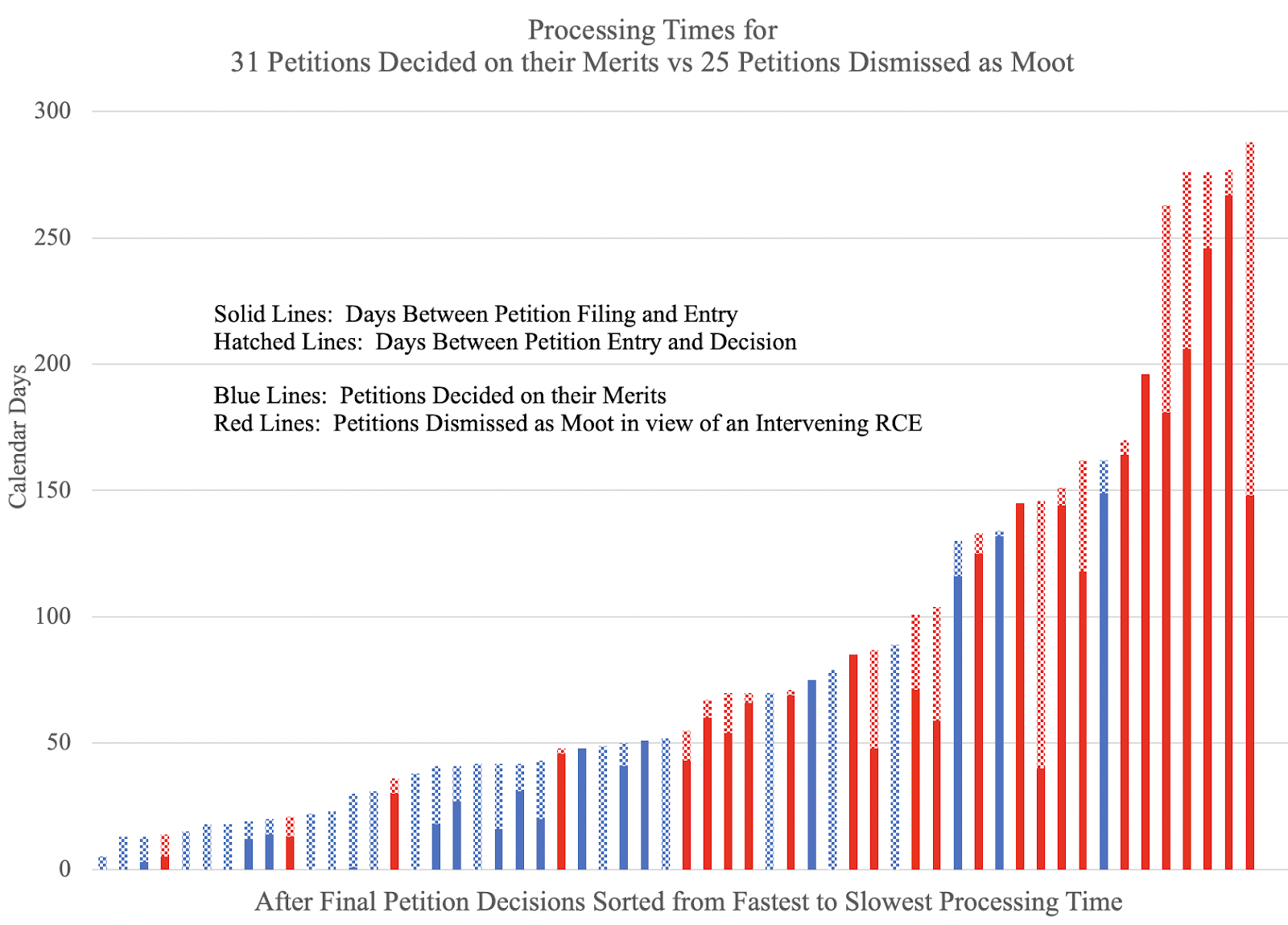

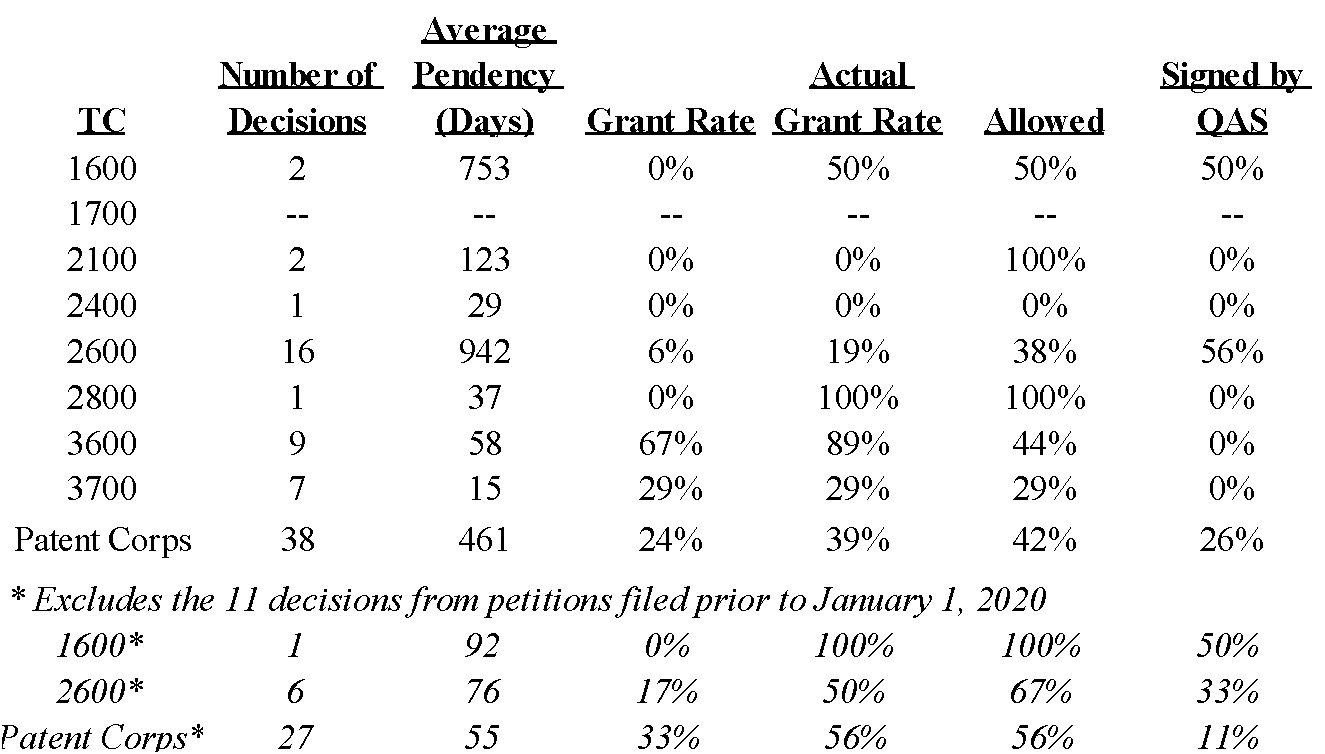

Curious as to why the pendency numbers dramatically increased during the fourth quarter of 2020 for petitions related to premature final rejection, we performed a search of Petition.ai’s database using the newly added Petition Type filter – Prematureness of Final Rejection – and easily identified 38 such petitions. Together, these petition decisions had an excessively high pendency of 461 days, as compared to the prior 12-month rolling average processing time of 80 days.

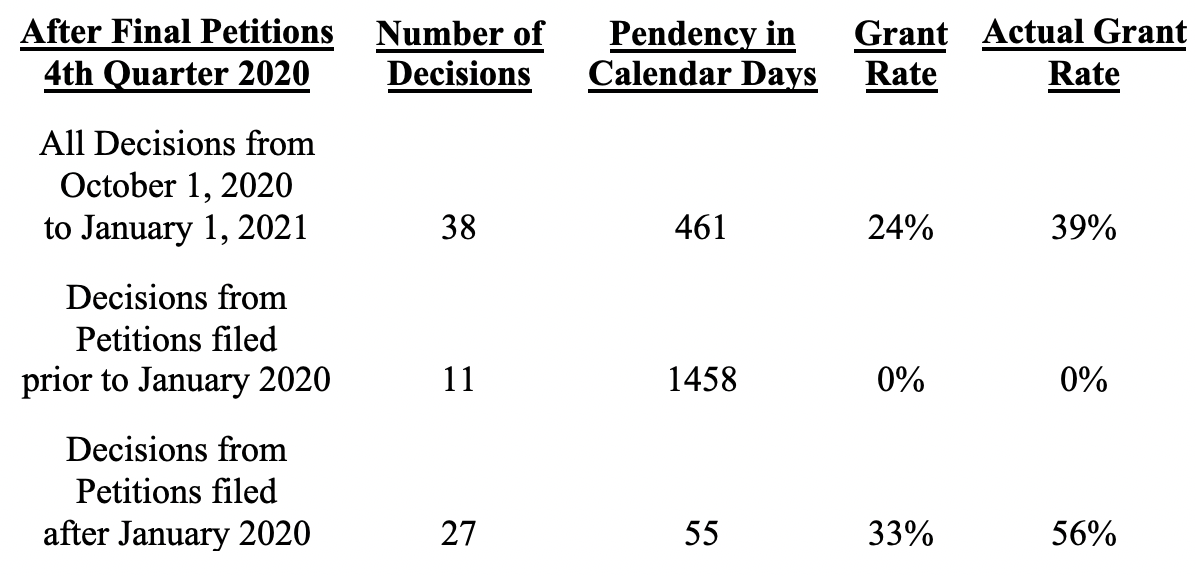

Table 2

We noticed a bimodal distribution of decisions. Recently-filed petitions were processed in an average 55 days, while petitions filed prior to January 1, 2020 were processed in an average of 1,458 days, i.e., 4 years! Moreover, we see 100% of these late decisions are dismissed or denied since the applicant would have been forced to file RCEs or Notice of Appeals three-plus years ago to save their applications from abandonment.

When all 11 of the petitions filed prior to January 1, 2020 are included, the pendency average was an unfeasible 461 days. Excluding these 11 decisions from the averages, the remaining 27 petitions filed after January 1, 2020 were decided on average in 55 days, less than two months, significantly better than the October 1, 2020 12-month rolling pendency data of 80 days. The decisions on the old petitions dramatically skewed the pendency data. This means, for recently filed petitions, practitioners are actually receiving petition decisions well in advance of their six month response time.

In addition, we found petitions filed after January 1, 2020 were treated differently on their merits. These 27 decisions had a 33% grant rate. We reviewed the electronic file records of applications containing dismissed petitions and determined that, in many instances, the actual outcome was favorable for applicants. Decisions labelled as dismissed masked favorable outcomes where the Examiner had sua sponte withdrawn finality or issued a notice of allowance in advance of the petition decision. Table 2’s column “Actual Grant Rate” shows a 56% chance for a favorable result for recently filed petitions challenging a premature final Office action, significantly higher than the USPTO published grant rate of 41%.

As we tried to figure out how the bimodal distribution came about, we made a call to the USPTO Quality Assurance Specialist (QAS) involved with many of the petitions filed before January 1, 2020. On April 7, 2021, the QAS informed us (paraphrasing) “the Office turned on a new petition tracking system which highlighted old petition requests that hadn’t been decided. A bunch of old petitions were decided in late October/early November.” If the Office is clearing a backlog of old undecided petitions, then we would expect to see the rolling average drop over time back to at least the 70-80 day range. Of course, we only know of the petitions which have been decided and are not privy to any other backlogs of undecided petitions. Anecdotally, the April 1, 2018’s rolling average of 184 days had also been attributed to clearing of a backlog of old petitions. However, that backlog clearance initiative apparently did not identify petitions pending at that time which were dismissed years later in the fourth quarter of 2020.

Because the USPTO’s pendency jump appears unique to petitions pertaining to premature final Office actions, we speculate that either backlogs had not built up for other types of petitions decided within the Technology Centers or that this new petition tracking system only identifies petitions challenging premature final Office actions.

Massive variation of pendency data and outcome by Technology Center

We next sorted these decisions by Technology Center (TC). We found the majority of the TCs decided petitions within 15-58 days. However, between October 2020 and December 2020, two TCs (TC1600 and TC2600) decided after final petitions in an average of two plus years. Interestingly, after excluding the 11 petitions the TCs finally issued decisions to clear their backlog, TC1600 and TC2600 decided petitions in 92 days and 76 days, respectively.

We also noticed the Deciding Official for the petitions filed prior to January 1, 2020 was often a QAS. This seems in contrast to MPEP 1002.02(c)3(a)’s requirement that the authority to decide these types of petitions is delegated to TC Group Directors and raises the question as to whether Group Directors are even aware of these old petitions.

Table 3

Petitioning Does Not “Poison the Well”

Moreover, consistent with our findings in Part V, Table 3 shows petitioning an Examiner’s action does not “poison the well”. Regardless of whether the petition is granted, dismissed or denied, we have found petitioned cases often go on to issue. In Table 3, we found 42% of the applications with recently decided petitions have already received a Notice of Allowance. Excluding the 11 petitions filed prior to January 1, 2020, 56% of the petitioned applications have already received a Notice of Allowance.

Office of Petitions Responds

As we dug deeper into the results obtained in Table 3, we asked the Office of Petitions about the relationship between petitions decided in Technology Centers and the Office of Petitions as well as whether the Office of Petitions oversees the process of how petitions are decided in Technology Centers. The Office of Petitions responded:

Although the Office of Petitions processes petitions to review a decision of a Technology Center Director, the Office of Petitions generally does not oversee the process of how petitions are decided in the Technology Centers. Also, the Office of Petitions coordinates/collaborates with the Technology Centers on various matters, but generally does not keep track of petition decisions at Technology Centers.

The Office’s response is consistent with our results showing great TC-to-TC variation in petition pendency and grant rates. Consistent with our results shown in Table 3, the USPTO apparently gives each Technology Center the discretion as to when and how they choose to process petitions, and even who has authority to decide such petitions. This results in significant TC-to-TC variation in standards of review, petition pendency, and grant rates making it difficult for practitioners to know what to expect when filing similar types of petitions in various TCs.

For example, TC3600 and 3700, both in the Mechanical discipline, have vastly different petition processing practices. In the fourth quarter of 2020, TC3600 decided nine petitions within 58 days, with an average 89% actual grant rate. In contrast, TC3700 decided seven petitions in 15 days, however, the actual grant rate was only 29%. Because the assessment (whether an examiner’s determination of finality is appropriate or not) should be strictly procedural in nature, significant TC-to-TC variation in after final petition pendency and outcome suggests non-uniform application of the USPTO’s procedural requirements, either by Examiners who make Office actions final or by the officials who review these kinds of petitions.

Don’t Let the USPTO Statistics Fool You into Not Filing a Petition

Practitioners who review USPTO statistics may be falsely led to believe that their inventors have no chance of obtaining a petition decision in advance of their six-month statutory response time. And, if they do obtain a decision, it will likely be negative. The USPTO dashboard statistics – 180 plus day pendency with a 42% grant rate! – may scare off some applicants who would otherwise exercise their right to challenge a premature final Office action on petition. In actuality, our results show recently filed petitions are being decided in an average of 55 days, with a 56% actual grant rate. Moreover, the USPTO dashboard statistics mask a significant amount of TC-to-TC variation. Drilling into the TC-level data, we identify some TCs which decide these kinds of petitions significantly faster than (15 days in TC3700) and more favorably than (as high as a 89% actual grant rate in TC3600) other TCs. This information can help patent practitioners gauge their chances for a positive outcome when deciding whether to challenge a premature Office action by petition.