USPTO Flexes Its AIA Powers To Make Retroactive Substantive MPEP Policy Changes

Originally published on IPWatchdog

Julie Burke, Ph.D.

Retroactive guidance complicates adjudication, making it difficult to determine what the proper procedure was on any particular date. Clarity is lacking when examiners and patent practitioners are literally not working off the same page.

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) publishes the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP) (currently electronically, but spanning thousands of pages in printed form) to provide examiners and patent practitioners with guidance on the patent statute, USPTO regulations, and patent prosecution practices and procedures. USPTO regulations are promulgated pursuant to the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), which requires a process that includes publication of proposed rules and a public comment period and are binding on the public. The MPEP is generally considered to be agency guidance that does not have the force or effect of law, and even though published by the USPTO, changes to the MPEP do not necessarily involve public notice or comment. However, the manual has a substantial impact on the patent examination, steering examiner behavior and placing obligations on practitioners to such an extent that it is commonly cited in U.S. Court of Appeal for the Federal Circuit opinions. The latest revision, E9R-07.2022, announced in a March 2023 Federal Register Notice, raised initial concerns about retroactive policy changes that ran counter to executive and congressional goals.

The 2011 Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA) strengthened the USPTO’s already-considerable policymaking powers. In a recent law review article addressing the USPTO’s post-AIA policymaking powers, William Neer recognized the USPTO’s AIA-empowered potential to engage in retroactive substantive rulemaking and determined that the USPTO promulgated more rules post-AIA than it did pre-AIA. This article discusses substantive MPEP procedural changes implemented retroactively by the USPTO.

Prior to 2014, the MPEP Followed Traditional Publication Processes

From its establishment in 1949, the MPEP was updated every few years by publications that had until recently followed a long tradition. From 1953 to 2012, the Foreword of each new revision of the MPEP stated:

Orders and Notices still in force which relate to the subject matter included in this Manual are incorporated in the text. Orders and Notices, or portions thereof, relating to the examiners’ duties and functions which have been omitted or not incorporated in the text may be considered obsolete. See 2012 Foreword.

Beginning 2001, the Foreword listed specific USPTO Orders and Notices, including memos, which were incorporated into that edition of the MPEP. The Blue Pages listed specific changes marked as follows:

Additions to the text of the Manual are indicated by arrows (><) inserted in the text. Deletions are indicated by a single asterisk (*) where a single word was deleted and by two asterisks (**) where more than one word was deleted. The use of three or five asterisks in the body of the laws and rules indicates a portion of the law or rule that was not reproduced. See 2012 Blue Pages.

In 2014, without public notice and comment, then-Director Michelle Lee quietly imposed several important changes on the MPEP revision process itself. These changes included:

- The Foreword stopped identifying specific Orders and Notices, including memos, that were the basis for MPEP changes

- the Foreword stopped stating that any Order, Notice or memo not included in the MPEP may be considered obsolete, creating uncertainty as to its status

- the Blue Pages were replaced by a Change Summary which discontinued the practice of providing revision marks to show text added or removed

- for the first time in its history, the MPEP published with changes that did not initially become effective on the date of publication.

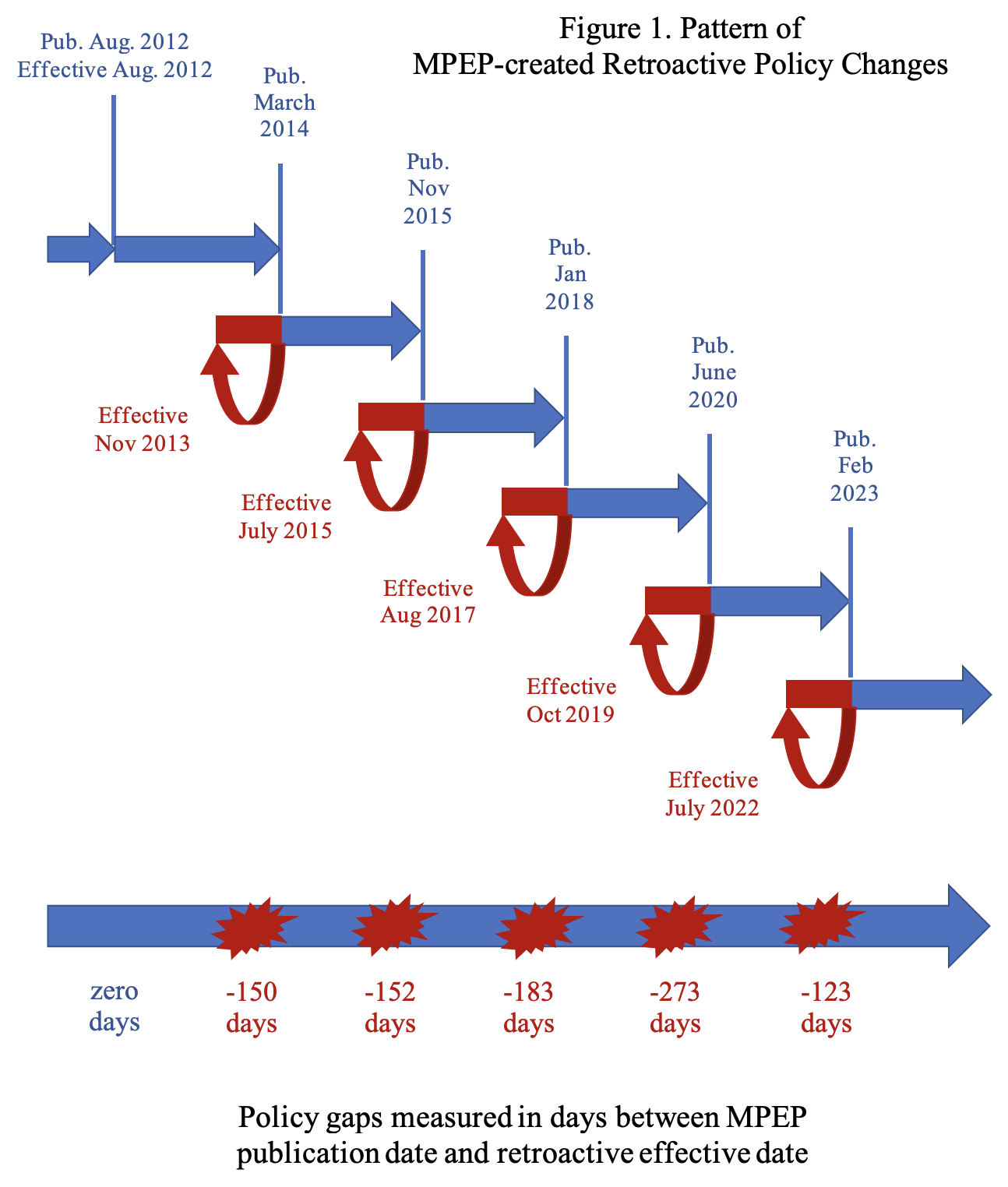

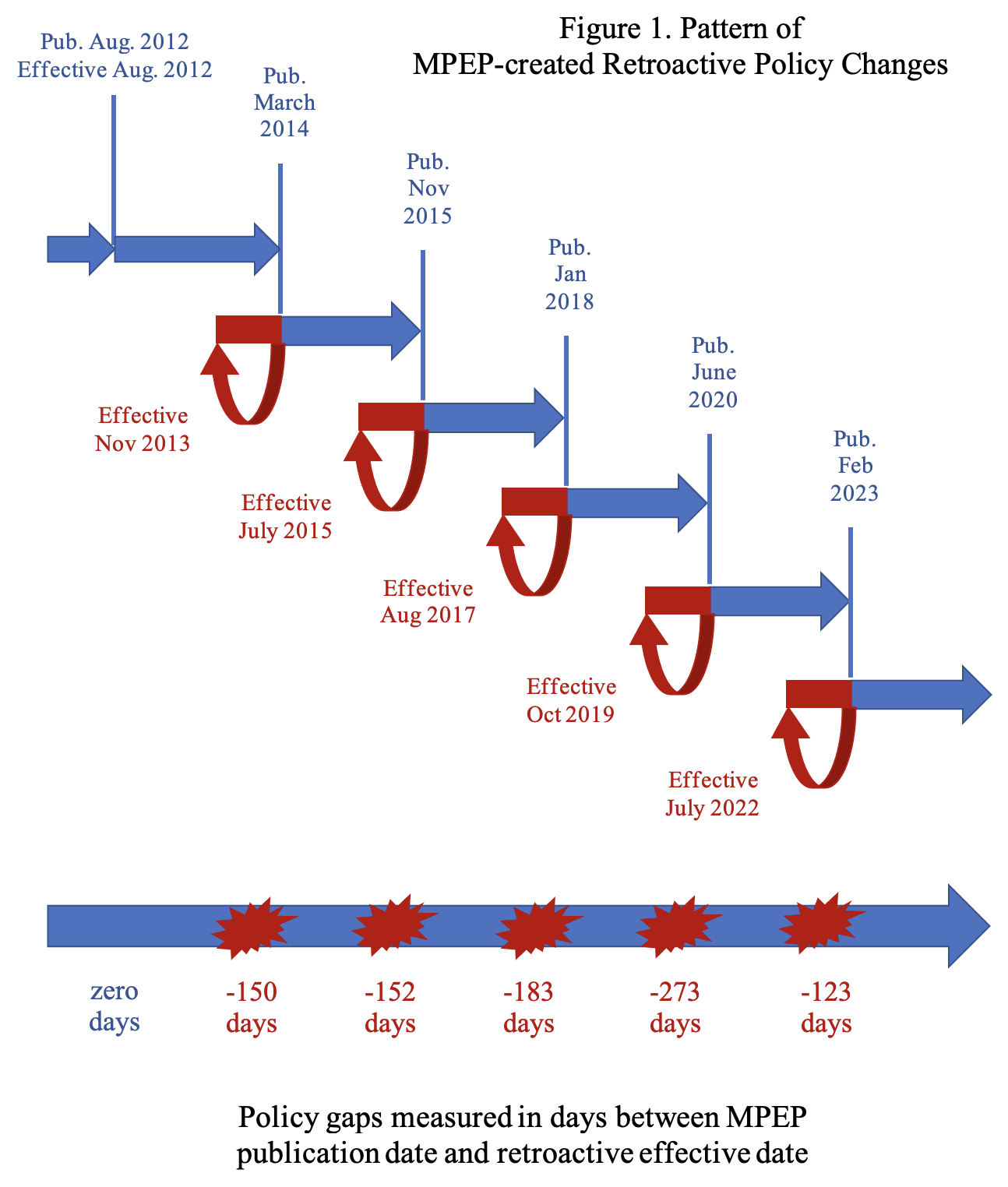

Instead, the MPEP published in March 2014 introduced changes in policy and procedures, including form paragraphs available to examiners that had become effective November 2013. The USPTO has revised and published the manual five more times since then in a similar manner. The latest version, published February 2023, includes changes that had internally become effective on or before July 31, 2022. See 2023 Change Summary.

Does the MPEP’s Revision Process Provide Clarity as to Existing Regulations?

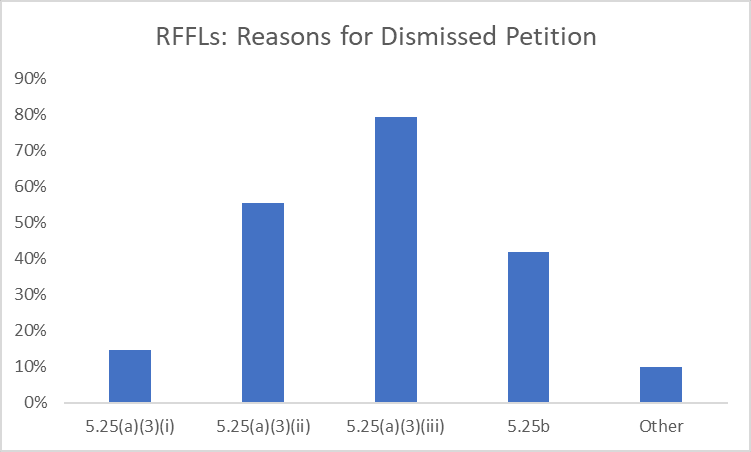

The 2014 Foreword indicates that the manual is meant “to provide clarity to the public regarding the existing requirements under the law or agency policies.” However, it is difficult to square that laudable goal with the current policy of making retroactively effective policy changes, which seems to contradict the goal of providing clarity regarding the existing regulations, and directly counter to the law’s deeply rooted presumption against retroactivity. The impact of this publication policy over the past decade is illustrated in Figure 1, identifying large gaps of time during which the USPTO operated under secret internal policies that patent practitioners were not privy to see until months later.

For 25% of the time, between November 2013 and March 2023, users of the MPEP relied on outdated instructions, guidance and requirements that would be later retroactively overwritten by a subsequently published manual. These policy gaps are important for patent prosecutors who are obliged to prepare applications and respond to Office requests based upon the USPTO’s current policies and procedures. These policy gaps are also important for litigators reviewing patent file histories to determine whether the patent examiner or applicant had correctly followed USPTO’s procedures on any particular day. Retroactive guidance complicates adjudication, making it difficult to determine what the proper procedure was on any particular date. Clarity is lacking when examiners and patent practitioners are literally not working off the same page.

Caveats and Cautions

MPEP webpage versions do not include the publication date. PDF versions contains both publication date and effective date. Publication date and effective date are misnomers, since publication and revision indicators provide only month and year, leaving readers to guess as to which exact date the changes were published or became retroactively effective. Here, MPEP revisions are referred to by publication year and the first day of each month is used as proxy for “dates.” The October 2015 publication, named E9R07.0215, replaced by a November 2015 version also named E9R07.0215, has not been considered.

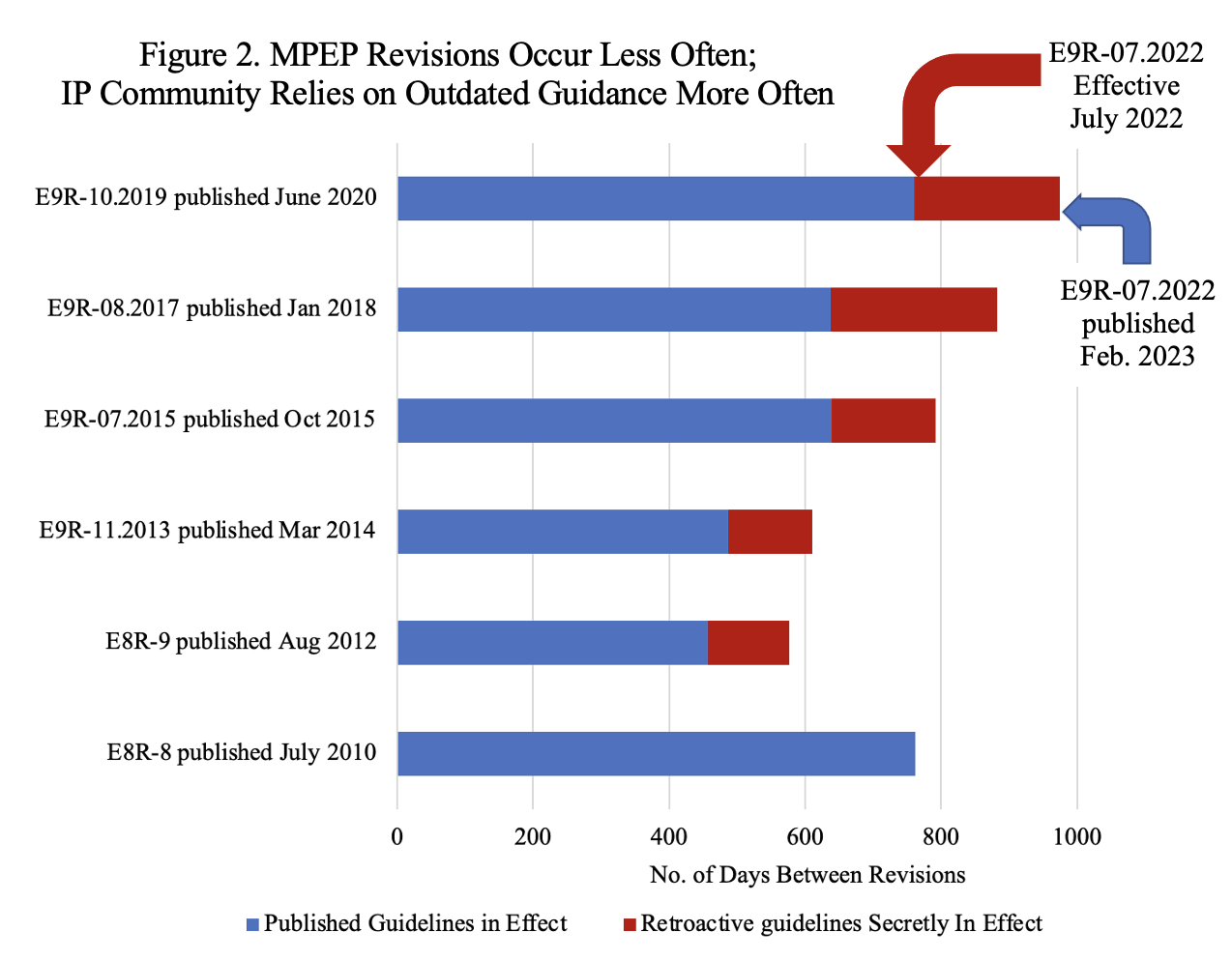

Is the USPTO Issuing More Frequent MPEP Updates?

The USPTO revised its process in 2024 “in order to…issue more frequent MPEP updates…The new publication process will improve the ability of the USPTO to timely publish single topic revisions to the MPEP, such as in response to judicial decisions that are determined to require rapid changes to examination policy.” See 2014 Change Summary. Yet, since 2018, the time between MPEP updates and the lengths of retroactive policy gaps have grown. Figure 2 shows that the 2014 revisions to the publication process did not meet the USPTO’s stated goal of issuing more frequent updates.

The Growing Monster

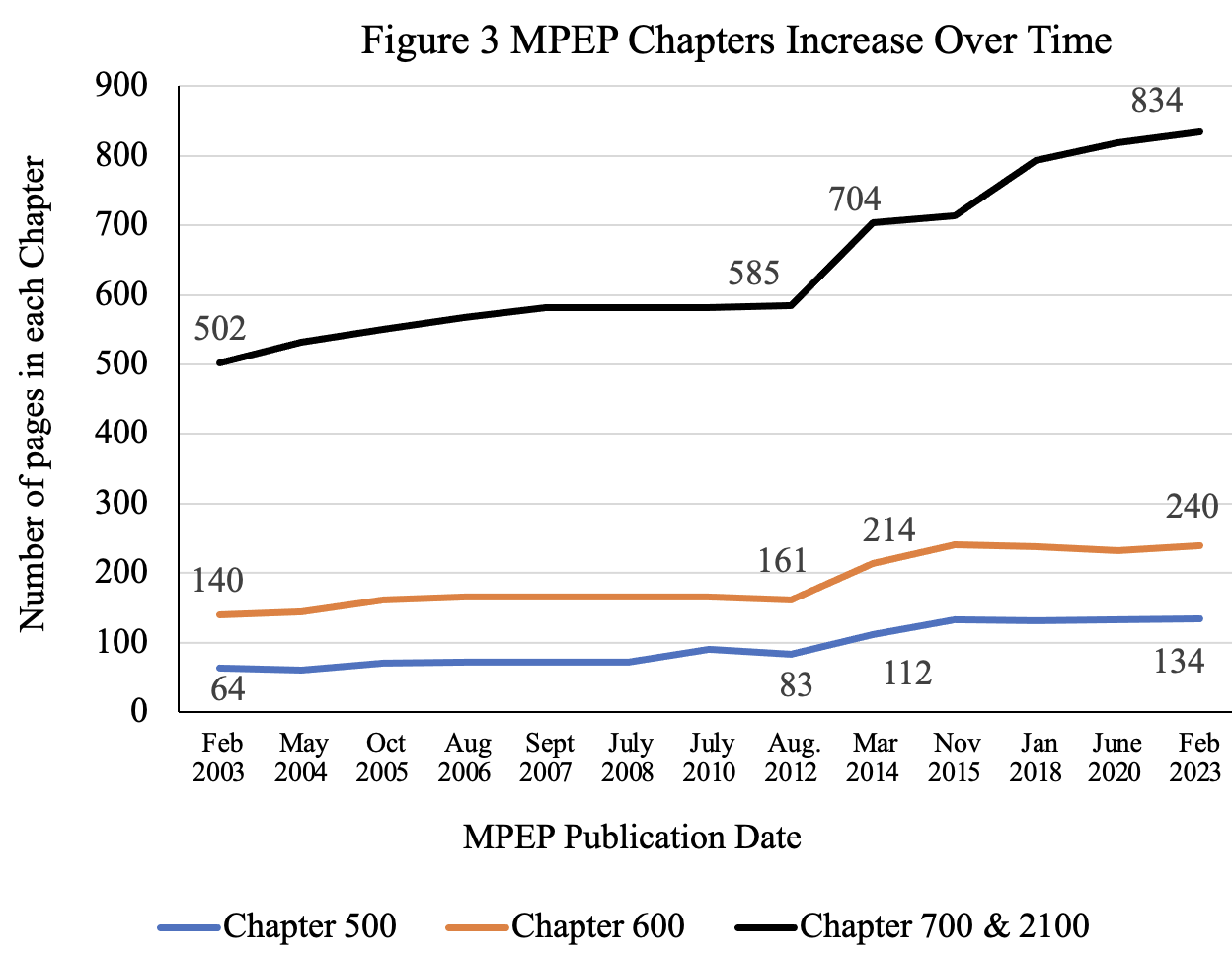

The size of the MPEP has also increased. Patent examination and prosecution have never been a simple process. The 1949 First Edition was 215 printed pages long. By 2014, the MPEP had become a burgeoning behemoth. New guidance and procedural requirements imposed since have resulted in steady growth of MPEP chapter sizes shown in Figure 3.

Extensive and Substantive Policy Changes Made via MPEP Revisions

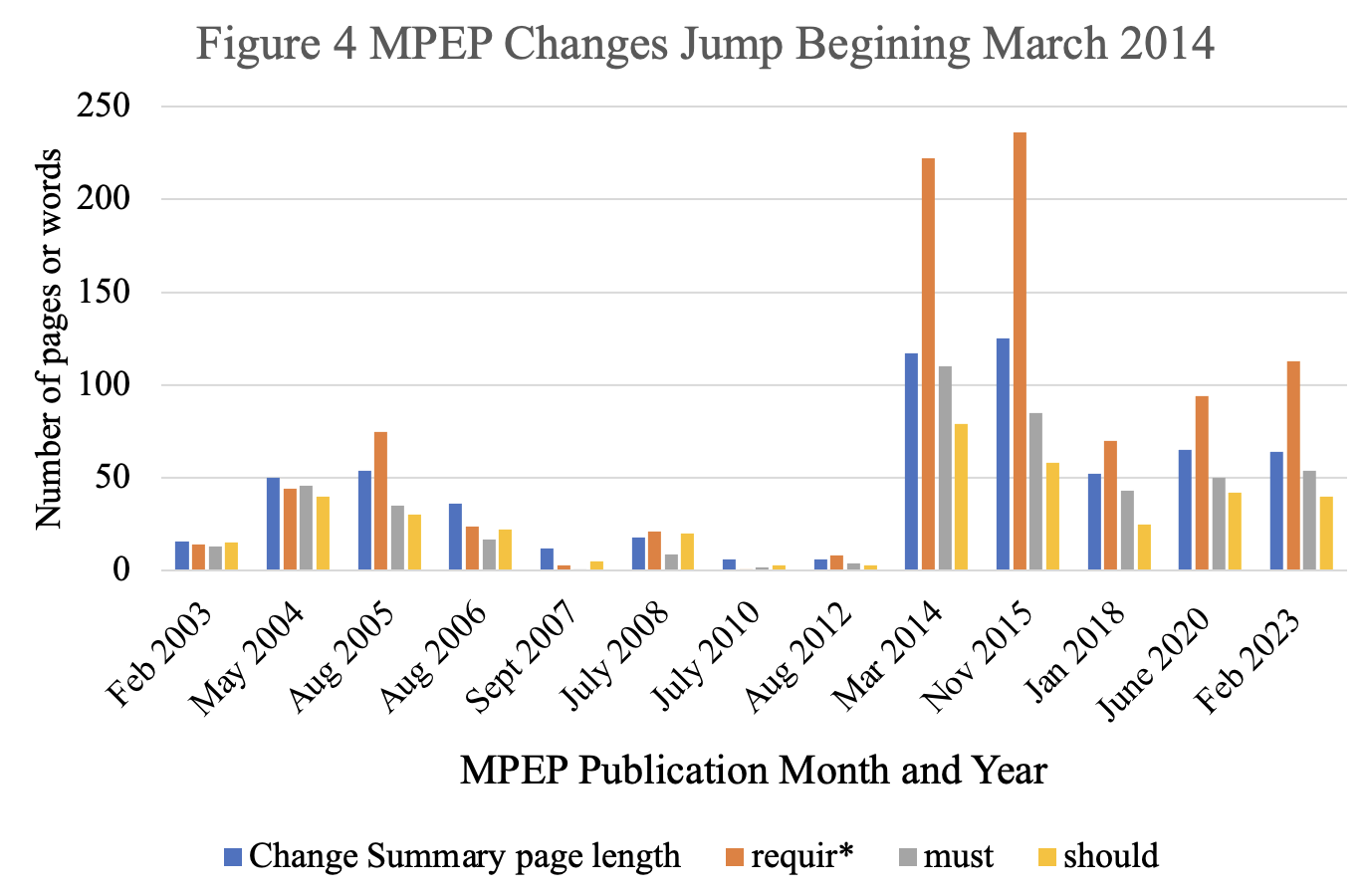

Because the Change Summary and the pre-2014 Blue Pages intermix substantive procedural changes with long lists of minor changes, page length was used in the analysis below as a rough proxy for the number of procedural changes. The incidence of terms “must,” “should” and variations of “requir*” which suggest new obligations or constraints on patent practitioners and new authorities given to patent examiners, were tallied for each Change Summary or Blue Pages. Figure 4 shows that beginning in 2014, the number of changes made in each revision jumped dramatically.

In 2012, nine memos were incorporated and the Blue Pages used the term “must” four times. In 2014, one memo was added, however the Change Summary used the term “must” 110 times. Similarly, the number of “should” and variations of “requir*” dramatically increased following the 2014 revision process changes. This suggests that since 2014, the USPTO has been imposing more and more new procedural burdens on practitioners and more options for examiners by way of MPEP revisions. Some of these procedural requirements result in substantive changes from the norm.

More Efficient for USPTO, Less Efficient for IP Community

The 2014 Change Summary indicates that the process for updating the MPEP was revised “in order to more efficiently use its new electronic publication tools…” Because revision changes are no longer identified using markings, a tremendous burden is placed upon practitioners to try to clearly identify revised policies. Some onerous policy changes could easily be overlooked, since they could involve addition of one or two seemingly innocuous words, as shown here in Table 2.

The MPEP Creates New Legal Consequences for Past Actions

Since 2014, several MPEP changes gave examiners more procedural tools to limit examination.

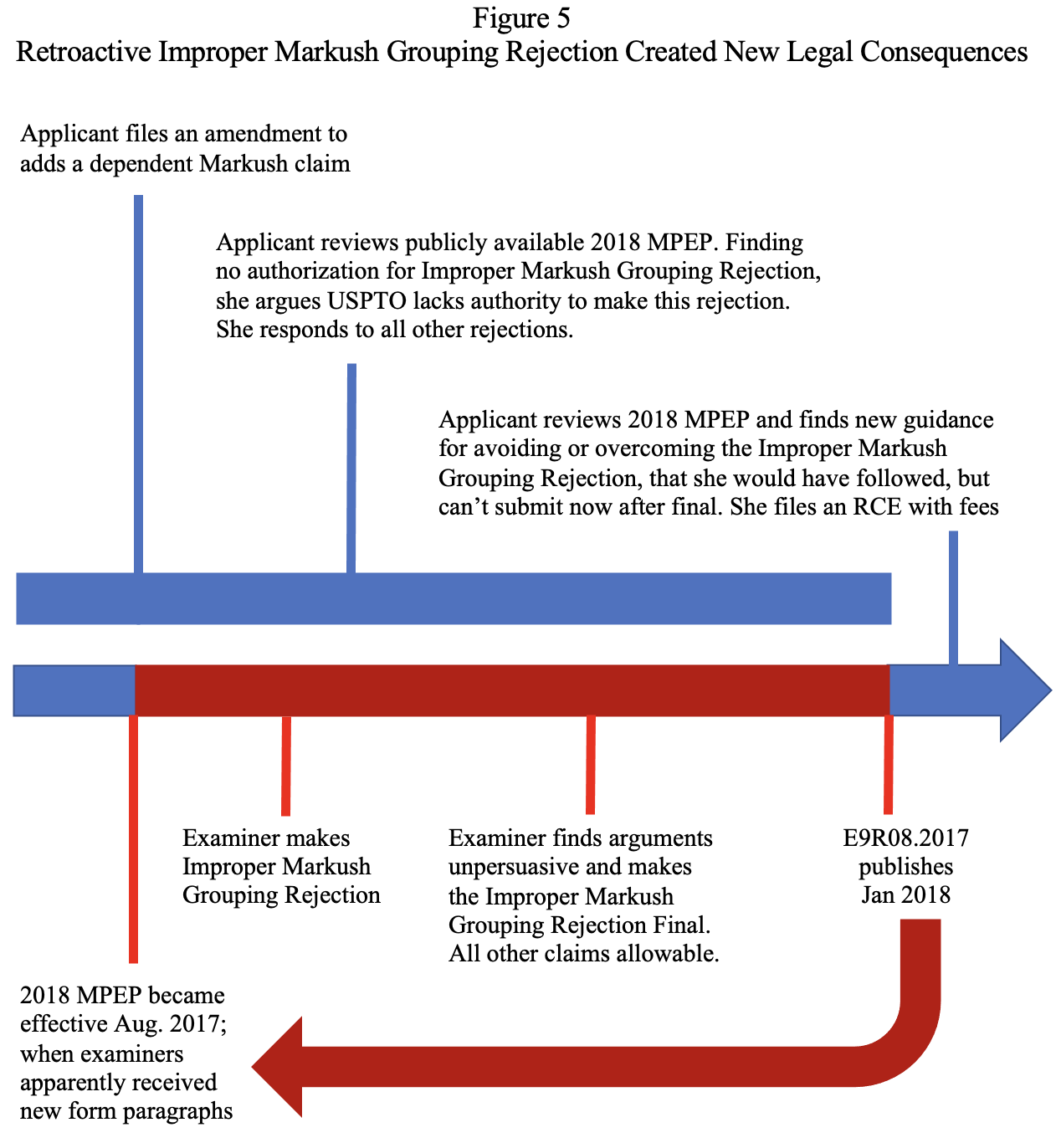

In 2018, Dr Joseph Mallon exposed the new “Improper Markush Grouping Rejection” quietly added to Section 706.03(y) of 2018 MPEP. This authorized examiners to reject generic Markush claims for including an improper listing of alternative elements. In 2011, the USPTO had issued guidelines authorizing improper Markush grouping rejections. Because these guideline were not incorporated into the 2012, 2014, or 2015 MPEP revisions and because the analytical framework was found lacking by the PTAB, practitioners considered them essentially obsolete. Seven years later, without notice, applicants began receiving new legal consequences on past actions: improper Markush grouping rejections on claims filed prior to the 2018 MPEP’s effective date. Applicants had limited ability to anticipate, avoid or overcome such rejections until Section 706.03(y) published five months later. See Figure 5.

If applicants had known of the new policy, they could have avoided or overcome the improper Markush grouping rejection and subsequent Request for Continued Examination (RCE) by presenting the claim in proper Markush format, arguing the merits of the rejection per guidance in 2018 MPEP, or authorizing the addition of the dependent Markush claim at time of allowance via an examiner’s amendment or filing a 37 CFR 1.132 amendment after allowance. But because applicants were not informed at the time the August 2017 implementation of improper Markush grouping rejections became effective, they were unable to take any of these actions. These lost opportunities underscore the inherent unfairness of a retroactive policy change.

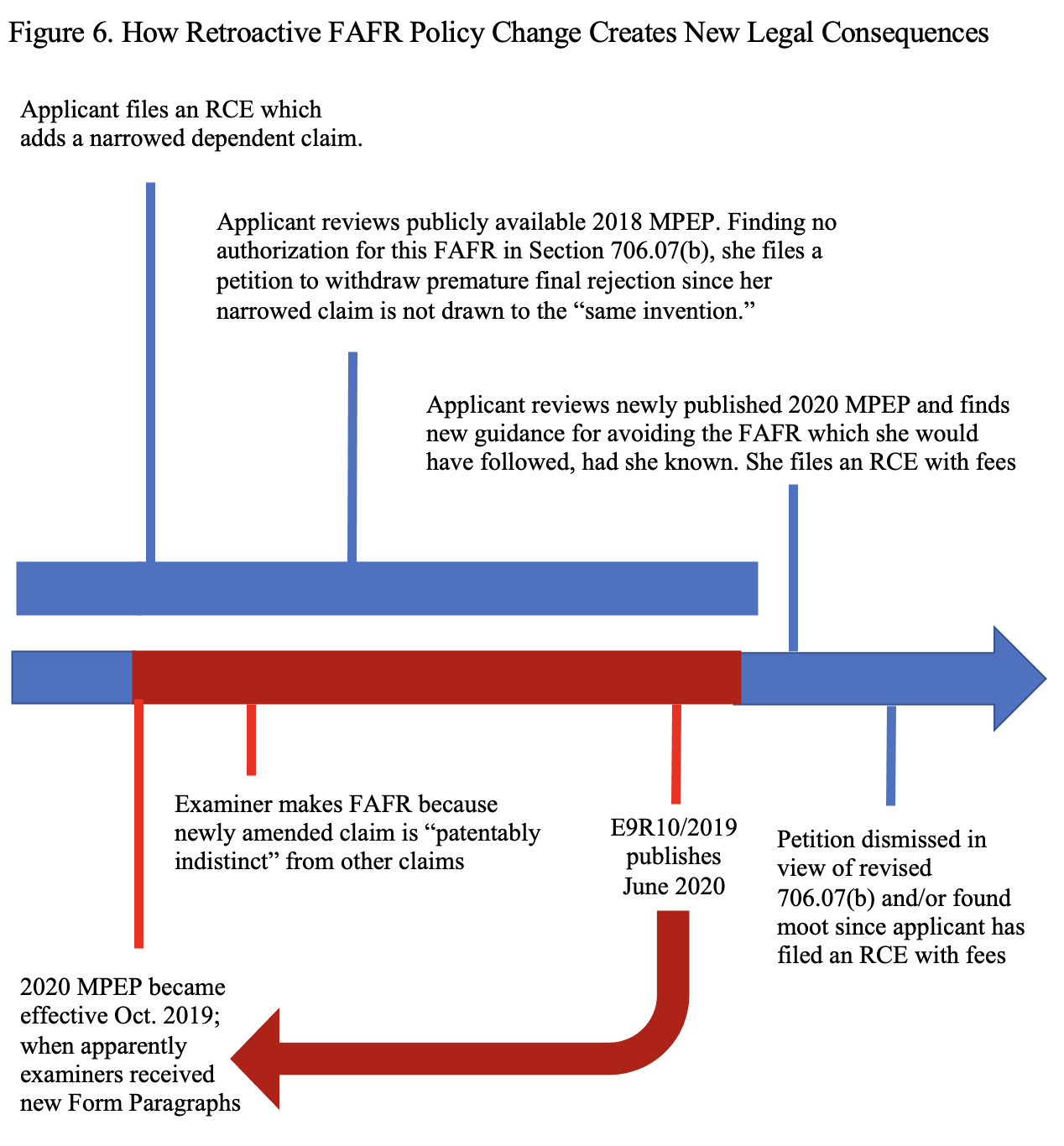

In June 2020, the USPTO changed MPEP 706.07(b) to broaden the first action final rejection (FAFR) criteria from “same invention” to “patentably indistinct” invention. This nuanced policy change substantially expanded the examiners’ discretion to issue a final rejection whenever the applicant files an RCE or a continuing application with no claim amendments or with amended claims that are patentably indistinct from ones previously examined. This change, made without any notice and comment, created new legal consequences for past actions shown in Figure 6.

Had applicants known about the Section 706.07(b) change, they could have avoided or overcome the FAFR by adding the narrowed claim after a first rejection or after a notice of allowance. More missed opportunities for applicants.

USPTO’s Notice and Comment Process is a Jumbled Mess

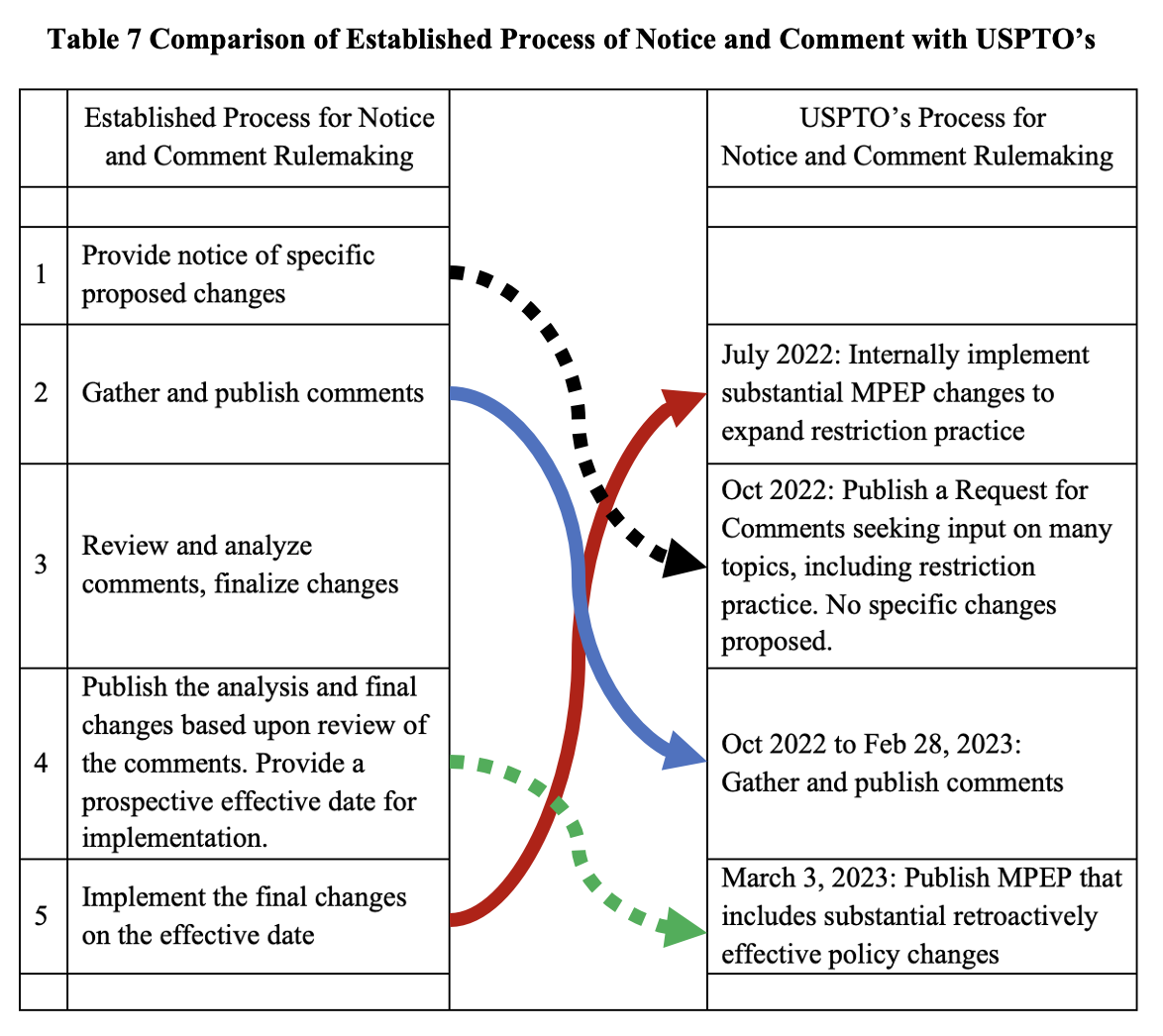

The USPTO can promulgate a retroactive rule, but only if Congress has specifically granted the agency power to do so. Congress has given the USPTO the right to retroactively grant foreign filing licenses. Neer urges the “best way to avoid promulgating retroactive rules is to engage in notice-and-comment rulemaking.” Unfortunately the USPTO’s notice and comment process is a jumbled mess. Table 7 compares the established process for providing notice and comments to the USPTO’s attempts.

For the 2023 MPEP, the USPTO did implement some of the steps required for public notice and comment, however these steps were not performed in the correct order or with required clarity. The Request for Comments (RFC) did not provide specific policy changes, rather it included open-ended questions concerning a wide variety of topics, including restriction practice. The RFC published after the MPEP had been revised to relax restriction policies. While the USPTO did gather and publish more than 225 comments, policies had already been effectively changed before the comments were analyzed. Notably, these retroactive MPEP substantive procedural changes were announced three days after the RFC public comment period closed. In their comments, the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice supported “[i]mproving examinations with a more rigorous and informed process [as it] will not only benefit the patent system but also help to ensure that competition is not harmed by the assertion of poor-quality patents. [Emphasis added] Certainly informing patent practitioners in advance of upcoming policy changes and publishing the changes in advance of the policy’s effective date would go a long way towards creating a more rigorous, informed and fair examination process.

Note: The author sent inquiries to the USPTO about the 2020 rule changes and the change to publication process post-2014 but had not yet received replies as of the time of publication.