How to Stop Examiners from Ignoring your Arguments

Originally published on MWZB

Ryan Pool

Compacting Prosecution And Petitions At The USPTO: Incredibly Useful And Incredibly Frustrating

Ryan Pool

Please click here to read a PDF version of the paper

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Higher Examiner Effort Equals More Compact Prosecution Achieved With A Particular Focus Being Given To The Use Of Petitions By Applicants

- The Levers Of Power

- Using Petitions To Cure Low Quality Office Actions

- The Consequences Of Examination Quality

- Applicants Use Of Petitions

- The Flaw In The System

- Where It Matters

- What Happens When The Petitions Office Gets It Wrong

- The First Amendment

- What Are Applicants To Do?

- Conclusion

Introduction

Increasing efficiency via compacting patent prosecution is generally something both the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) and applicants for a patent agree is a good thing. For applicants, compacting patent prosecution would mean saving significant costs and obtaining patents faster.1 With limited exception, this is something that all applicants desire.2 The USPTO has a publicly stated goal of achieving compact prosecution.3 The USPTO, in their own words, understands that “[a] failure to follow this approach can lead to unnecessary delays in the prosecution of the application.”4

Actually, achieving compact prosecution requires both parties to do their part. However, applicants are the primary parties injured in the form of lost time and money if it is not achieved. The USPTO provides incentive/disincentive structures designed to motivate or require Patent Examiners (“Examiners”) to fulfill their duties in pursuit of compact prosecution, but applicants also have their own procedural mechanisms for compact prosecution enforcement.

This Article explores these incentive structures and procedural mechanisms that can affect prosecution efficiency and seeks to evaluate their effectiveness, identifies problem areas, and suggests ways in which compacting prosecution might be better achieved with a particular focus being given to the use of petitions by applicants.

Higher Examiner Effort Equals More Compact Prosecution Achieved With A Particular Focus Being Given To The Use Of Petitions By Applicants

Compact prosecution is the practice of reducing the number of actions in a case before final disposal, i.e., either an allowance or abandonment. The USPTO seeks to achieve its compact prosecution goal by placing certain requirements on Examiners including an initial review of every claim for compliance of every statutory requirement for patentability and answering all response arguments received from applicants during prosecution.5 For the USPTO, compact prosecution is a procedural requirement which defines the minimum informational requirements for Examiners to provide during prosecution.6 In other words, on the USPTO side, achieving compact prosecution is primarily a matter of Examiner effort.

While the patent prosecution process is a cooperative process and applicants must also do their part to compact prosecution, it is fair and proper for applicants to expect that Examiners fulfill these minimum requirements of the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (“MPEP”) § 2103(I).7

Furthermore, a reasonable hypothesis is that if Examiners put a higher degree of effort into an Office Action, prosecution should be compacted to some greater degree.

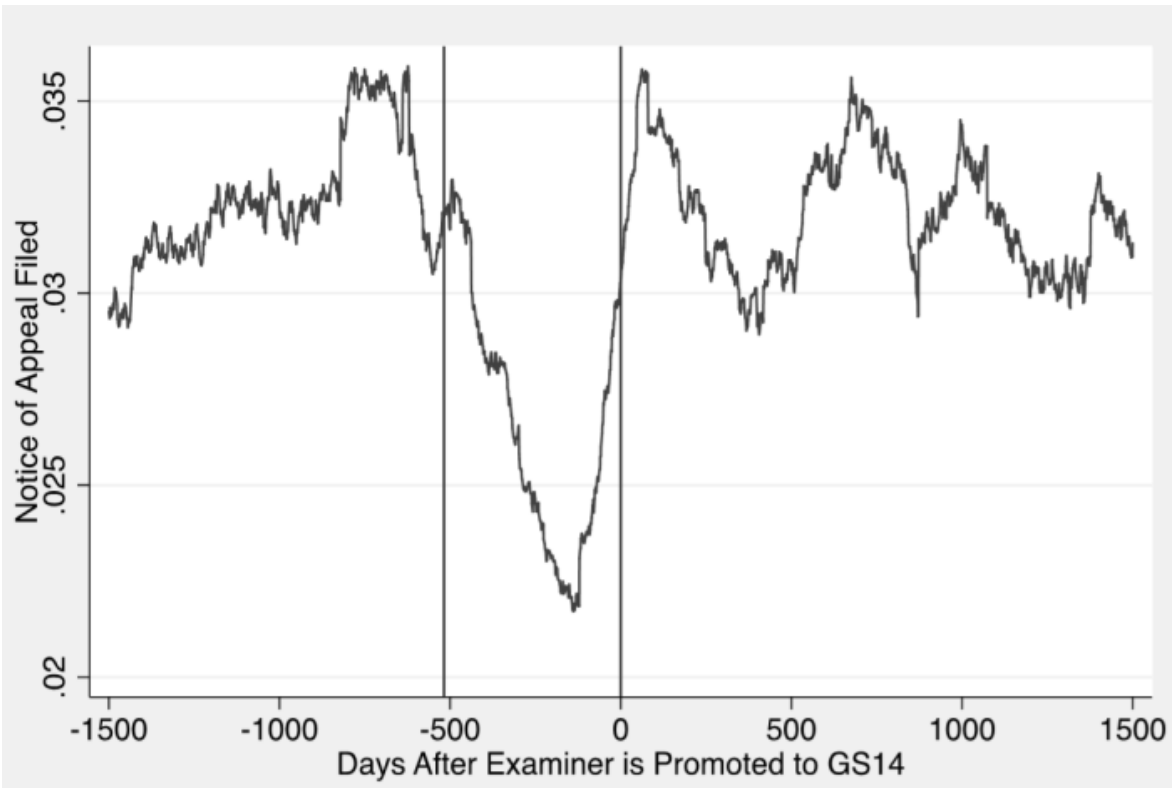

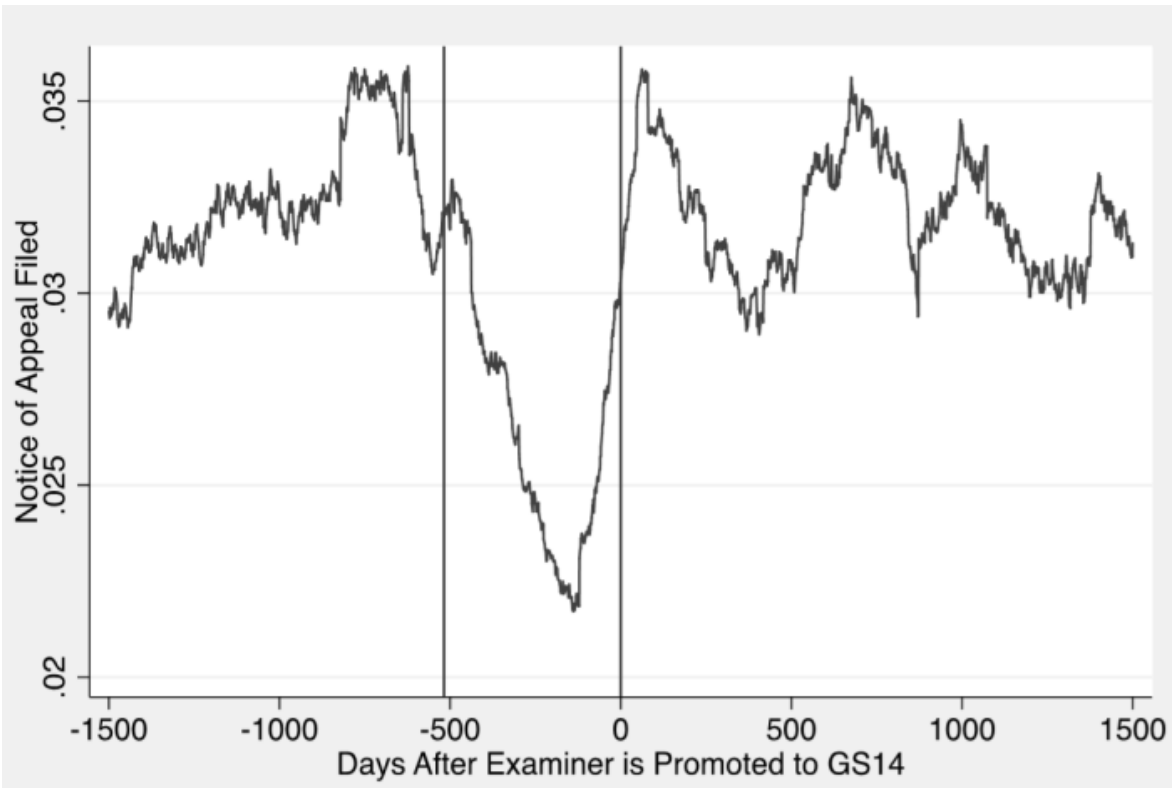

As evidence to support this hypothesis, Figure 1 tracks notice of appeal filings during and around the period a few years later where Examiners are in the Signatory Authority Review Program before being promoted to the General Schedule’s 14 payscale (“GS-14”).8 The Signatory Authority Review Program is an approximately two-year long period where the Examiner’s work undergoes greater scrutiny.9 Examiners presumably want to perform well during this period as their performance determines whether or not they will be promoted and receive increased compensation. Figure 1 therefore shows Examiners working in periods of normal and increased effort. The increased effort period is highlighted between -500 days and zero days after the Examiner is promoted to GS-14.10

Figure 1. Examiner Effort.11

Figure 1 shows that during the period of increased Examiner effort, a significant dip in notices of appeal are filed against them. While the decision to appeal often involves a complex weighing of different factors which varies from applicant to applicant, a common thread among these decisions is an applicant’s belief that at least some portion of the Office Action is erroneous.12 Figure 1 suggests that higher effort Office Actions result in low rates of applicant appeals, which presumably means a lower occurrence of applicants believing the Examiner has made an error which requires review from the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”). Notably, allowance rates also dip during the heightened Examiner effort period with a curve similar to that shown above.13 This means that the decline in appeals filed cannot be explained by the Examiners simply allowing more cases, giving the applicants less reason to appeal. In fact, the exact opposite is true. Therefore, at a minimum, the logical conclusion is that higher Examiner effort correlates with higher quality Office Actions.

It should not be surprising that when Examiners put more effort into their Office Actions, they produce higher quality Office Actions. However, the roughly 25% decrease in the amount of notice of appeal filings is rather significant. This indicates that increasing or decreasing Examiner effort can have a large impact on prosecution outcomes.

It is also a logical inference that higher quality Office Actions result in compact prosecution by more efficiently moving applications to final disposal. Reducing appeals alone would greatly contribute to prosecution efficiency. Appeals are among the least efficient procedures at the USPTO. Appeal pendency times are about 15 months on average and applicant office fees alone are about $3,000.14 Additionally, all things being equal, applicants are at least more capable of efficiently responding to higher quality Office Actions by making effective amendments, providing appropriate evidence, making targeted arguments, or more quickly determining that the application should be abandoned.

In summary, increased Examiner effort results in higher quality Office Actions and greater compacting of prosecution. If both the USPTO and applicants desire compact prosecution, and Examiner effort and higher quality Office Actions result in compacting prosecution, then one would logically expect that both applicants and the USPTO should be working together toward that goal. Two questions naturally arise. What are the USPTO and applicants doing to increase Examiner effort and examination quality? Additionally, is there anything more they could be doing?

The Levers Of Power

The USPTO has various ways of influencing the actions of its Examiners. However, its primary method is through its count system.15 The current count system sets the metrics for evaluating Examiner performance and affects everything from pay to continued employment, providing the main source of carrots and sticks to influence Examiner behavior. Quality of examination makes up 35% of the count system’s evaluation.16 The count system is not just concerned about quality, however, and must be balanced against things like production and docket management. For example, Examiners receive a monetary bonus for production above their goal and for keeping their application pendency below a predetermined level.17 Failing in either of these metrics can result in discipline.18

The USPTO evaluates the quality of examination by randomly sampling Office Actions in its quality assurance groups.19 Its goal is to review 12,000 cases a year.20 This is a rather small percentage of the whole.21 Therefore, an economically rational Examiner dealing with a scarcity of time to satisfy all the metrics of the count system could choose a strategy of quantity over quality. This strategy has the advantage of capturing potential monetary awards from both production and docket management and at least has a chance of avoiding penalties from a lack of quality, if the Examiner gets lucky with random sampling review.22

This strategy can be maximized by exploiting the limitations of the USPTO review system. The quality system essentially consists of reviewing randomly pulled cases for statutory errors, i.e., did the Examiner wrongly issue a rejection or miss a rejection they should have made?23 Such review has limitations of its own, however. For example, the most frequent error given to Examiners is missing an antecedent basis rejection while the least frequent error, almost never given, is missing an enablement rejection.24 This is not because the USPTO is currently stressing the importance of antecedent basis or that it is somehow more important but because antecedent basis is an easy issue for a reviewer to spot.25 It is easy to spot because antecedent basis can be reviewed by simply looking at the claims in isolation to see if they adhere to the rule. Compare this to enablement which requires review of not only the entire application, but also of the technology field in which the invention is positioned. The reviewers are not always trained in the technology they are reviewing, making this task exceedingly difficult.

An Examiner can increase the appearance of examination quality by focusing on easy to review portions of the Office Action while neglecting the more difficult portions, which unfortunately also tend to be more substantive, and are more likely to affect the ultimate enforceability of the patent. An economically rational Examiner would be motivated to expend far more effort looking for easier to review formality issues (like antecedent basis) rather than looking for more substantive issues, which are more likely to affect the ultimate validity of the issued patent claims. To prevent this, the USPTO could modify its review process to shift Examiner attention more toward substantive prosecution issues and less toward formalities, increasing its Office Action quality.

A separate factor when considering Examiner behavior is the amount of scrutiny an allowed or rejected patent application receives. Allowing an application calls down upon an Examiner much greater scrutiny than rejecting an application.26 Thus, low quality allowances are much less likely to be missed, compared to low quality rejections. This encourages lower effort rejections from Examiners which equates, in aggregate, to lower quality.

In total, while the USPTO cares about patent quality, it must balance this goal against others which sometimes conflict.27 Further, the USPTO’s methods for evaluating, enforcing, and incentivizing patent quality have their own biases and limitations.28 The result is limited incentives for Examiners to issue high quality rejections. Additionally, situations are created where sacrificing quality for, e.g., increased production, is in the Examiners best personal economic and employment interest.

Using Petitions To Cure Low Quality Office Actions

Applicants are not powerless to affect Examiner effort and Office Action quality. The USPTO offers applicants a remedy if they receive an Office Action which does not meet the minimum requirements of the USPTO’s compact prosecution goal.29 Under 37 C.F.R. § 1.181, applicants can petition the USPTO Director for a new complete Office Action if an Office Action does not comply with these requirements because it is procedurally incomplete.30 This could occur, for example, in a first Office Action where all claims of an application were not examined. However, this most commonly occurs after an Office Action response from applicants where the subsequent Office Action maintains a rejection but fails to address all of an applicant’s arguments traversing that rejection.31

Such a scenario specifically violates MPEP § 707.07(f) which requires, “[w]here the applicant traverses any rejection, the examiner should, if they repeat the rejection, take note of the applicant’s argument and answer the substance of it.”32 This rule clearly furthers the USPTO’s compact prosecution goals as the failure to answer the substance of applicants’ arguments results in the stagnation of that issue. This is because the applicant is left unable to progress prosecution as to this issue in their response because the Examiner has provided no new information to which they can respond.33 The appropriate remedy provided by the USPTO is withdrawal of the insufficient Office Action and issuance of a new Office Action which satisfies the requirements of MPEP § 707.07(f) and the USPTO’s compact prosecution goals.34

An additional side effect of this remedy is that it often creates Patent Term Adjustment (“PTA”) for the application.35

The Consequences Of Examination Quality

Increased examination quality not only results in compacting prosecution but also increased enforceability of issued patents.36 Issued patents which are later invalidated in litigation, for reasons that could have been prevented at the USPTO, create a real cost to the public as well as a negative public perception of the patent system as a whole.37

The appropriate use of petitions can therefore save applicants thousands of dollars per case and greatly expedite the time to final determination of allowance or abandonment by avoiding extra Office Actions, Request for Continued Examination (“RCE”) fees, and appeals. Furthermore, there are public benefits from increased patent quality, reduced unnecessary litigation, and increased perceived legitimacy of the patent system.38

The USPTO Office of Petitions can therefore serve two functions. First, it can be an important safeguard to compact prosecution and maintain procedural fairness for applicants. Second, it can function to lower the cost of unnecessary patent litigation and increase the public perception of the legitimacy of the patent system as a whole.

Applicants Use Of Petitions

A system can only work if it is used. However, applicants do not appear to be using 37 CFR § 1.181 petitions for a complete Office Action at a high rate. The data used in this Part was collected from Petitions.ai which has a searchable database of petition requests and decisions data mined from the USPTO PAIR/patent center.39

There were less than 100 petitions filed between 2018 and 2022 which requested a new complete Office Action based on an Examiner’s failure to issue a complete Office Action. Given the number of Office Actions issued over the fiveyear period observed—and assuming that Examiner work product falls on a normal distribution—this number of petition request appears rather low.40 Additionally of note was the relatively few numbers of law firms who filed any such petition at all. It would be rather extraordinary if only a select few law firms were being issued incomplete Office Actions. The combination of these factors suggests either a lack of awareness regarding the availability of the remedy among the general population of patent prosecutors or some additional externality dissuading the vast majority of prosecutors from filing such petitions.

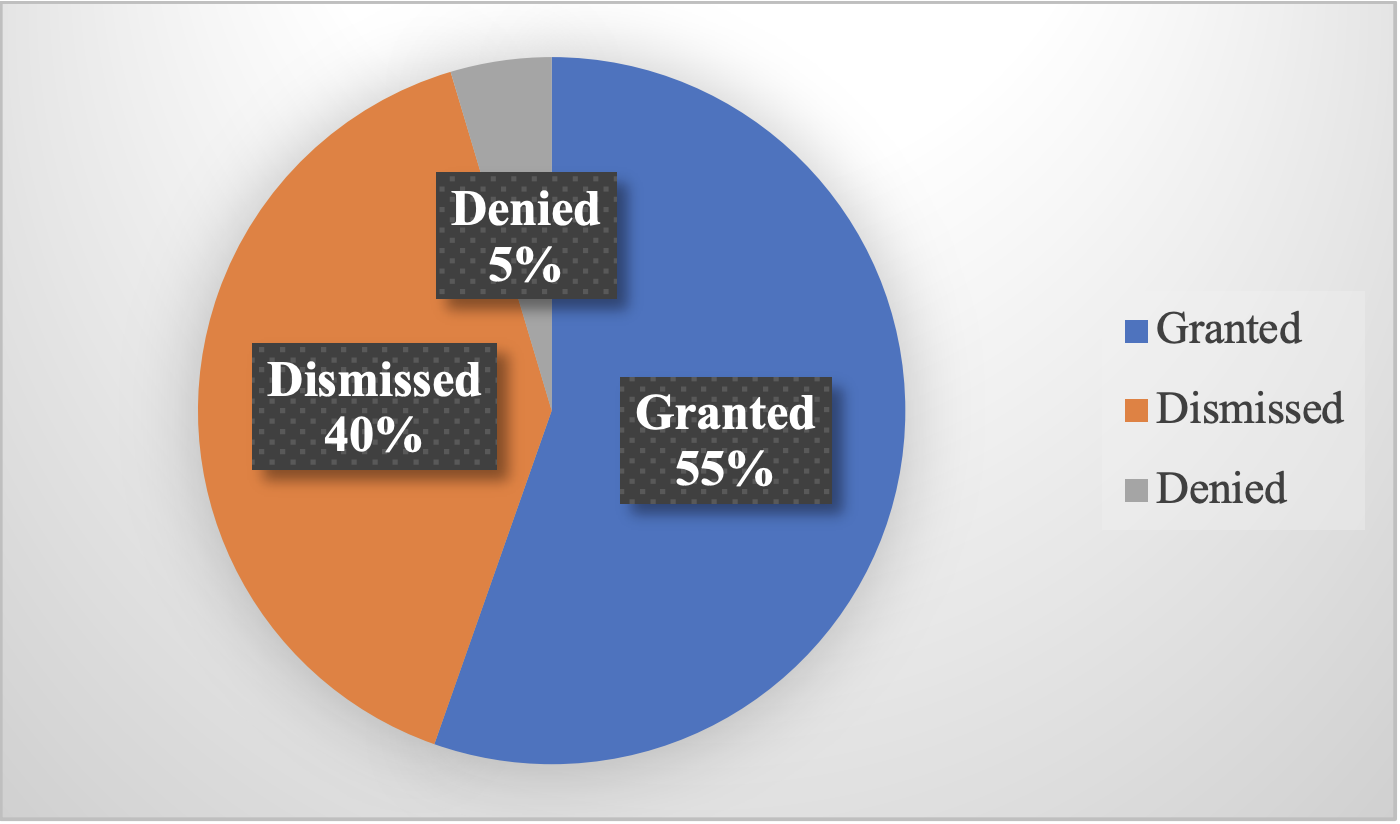

The number of decisions that were ultimately issued from these requests is even less than the number of requests as, presumably, some of these requests were dropped by applicants or rendered moot by a notice of allowance.41 The decisions which are issued are generally applicant favorable.42 However, while the majority of decisions granted applicants request for a new Office Action, about forty percent of the petitions were dismissed.43 A graphical representation is provided below in Figure 2.44

Figure 2. USPTO Decision on Petitions for New Office Actions Between 2018 and 2020.45

From review of the decisions from which the data above is provided, the reason for the high dismissal rates can generally be attributed to two main causes. First, the applicants petitioned for relief on a substantive issue rather than a petitionable issue. An examiner failing to respond to an applicant’s arguments is a valid ground for petition relief, while a disagreement between applicants and examiner on a particular issue must instead be appealed. For example, ignoring evidence of submitted unexpected results is petitionable, but finding that the evidence is not, e.g., commensurate in scope, even for ultimately incorrect reasons, is not petitionable. This issue must instead be appealed.46 This cause for dismissal appears to predominately be the fault of applicants. However, the second reason for dismissal is entirely due to the failure of the USPTO to efficiently process petition requests. Furthermore, this failure appears pervasive throughout all petition types.

The Flaw In The System

The USPTO has an unfortunate critical flaw in its petitions system. This flaw becomes apparent in instances where the USPTO is unable to timely issue a petition decision. The filing of a petition does not toll or delay the time period applicants have to respond to an Office Action.47 Therefore, if no decision on the petition is issued by the final due date for a response, applicants are forced to file an RCE or a Notice of Appeal in order to keep the application from going abandoned.48 To add insult to injury, such filings can (and do) in many cases trigger dismissal the petition.49

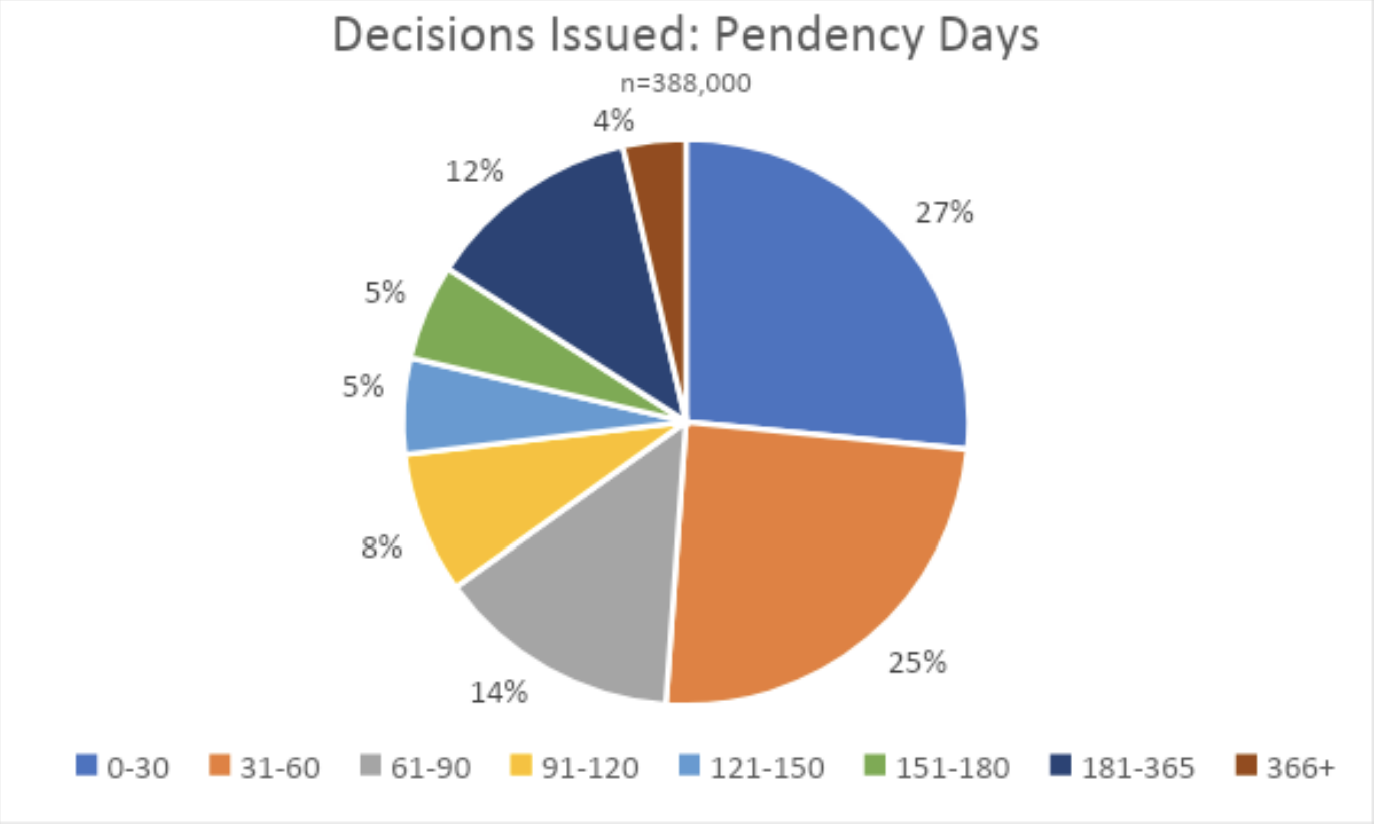

Figure 3 shows the pendency breakdown of 485,000 petition decisions issued from January 2013 to November 2021. It shows all petition types and their processing time broken into roughly month-long groups.

Figure 3. Petition Pendency.50

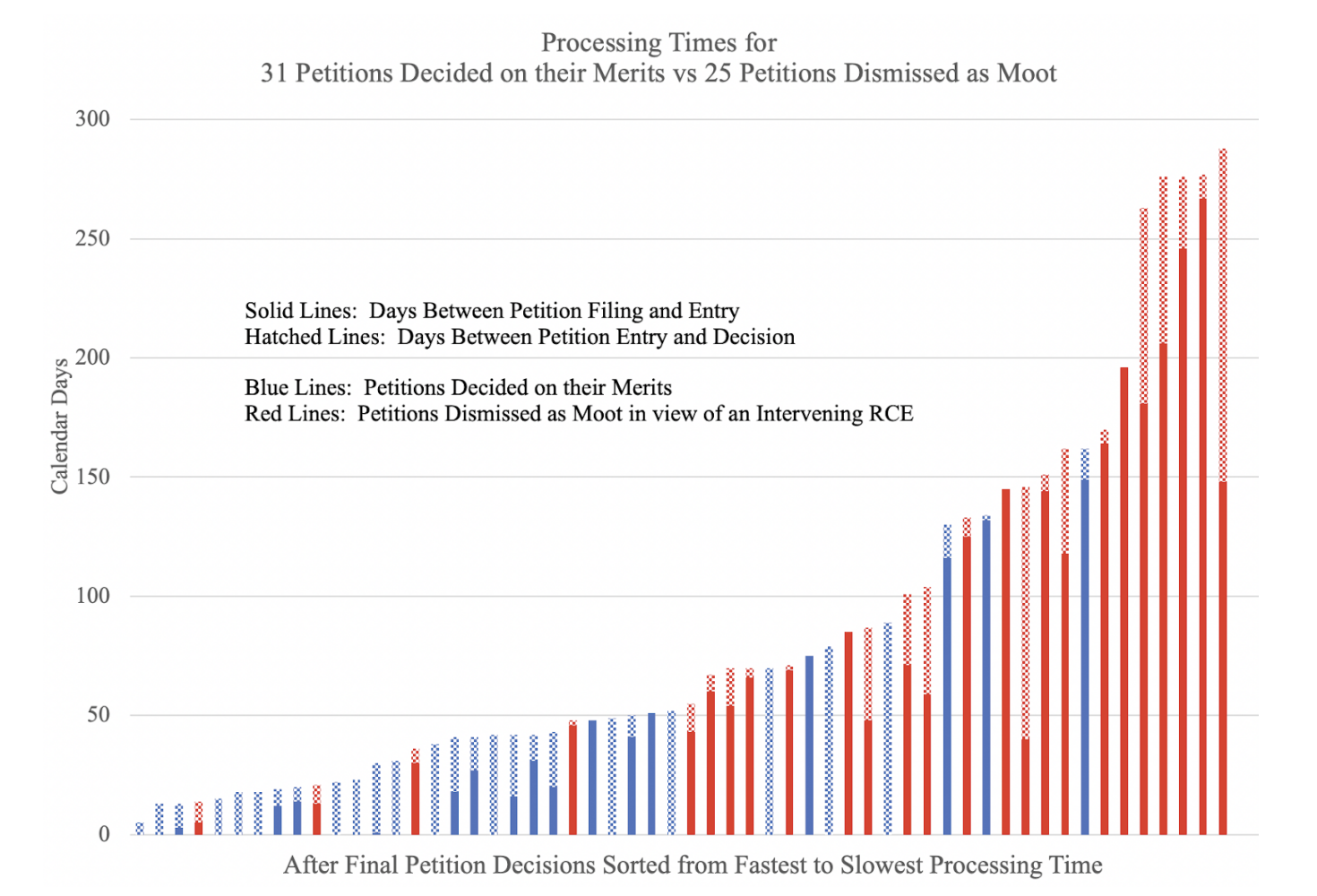

Zooming in to show what happens to cases where the processing time for the petitions is delayed, Figure 4 shows cases that were dismissed versus cases that decided on the merits ordered from fastest (left) to slowest (right) processing time.

Figure 4. Petition Processing Times.51

Figure 4 suggests around 121 days, or roughly four months, is the threshold for when delay becomes unreasonable on the part of the USPTO. For the relevant petitions to be timely filed, they must be filed two months from the mailing date of the Office Action. Even when paying for all applicable extensions of time, applicants have at most six months to respond to an Office Action. Therefore, when the USPTO delays more than 121 days, they are likely to run out the six-month clock on applicants even where applicants timely filed their petitions.

Figure 4 illustrates this, as almost all petitions which are delayed more than 121 days are dismissed as moot, the reason almost certainly being because applicants were forced to take action in the case which rendered their petitions moot, e.g., filing an RCE.52 That is, these RCEs and subsequent dismissals are being forced on applicants by USPTO delay.

Consider Figure 3 and Figure 4 in combination. Figure 3 shows that petitions delayed more than 121 days constitute 26% of all petitions filed.53 It is important to note that Figure 3 includes all petitions filed, including those which are essentially automatically granted without substantive review. This is mostly why the largest slice of the pie is zero to thirty days. In reality, petitions which require substantive review are likely being unreasonably delayed closer to about a third of the time.54

“Justice delayed is justice denied" is a legal maxim which applies here to the Office of Petitions.55 Based on the data presented, the USPTO is failing to timely process one in every three substantive petitions it receives. Furthermore, the USPTO offers no mechanism for forcing a timely petition decision or remedy for applicants when the clock is run out on them. By delaying a decision and then dismissing the petition as a result of applicants acting to prevent the abandonment of their application,56 the USPTO is disposing of the petition without addressing the issue of why it was filed. If the Office of Petitions is to effectively perform its duty, it must do so in a timely manner. When it fails in this critical task, it causes the exact harm to applicants which it is supposed to protect against which is additional fees for applicants and a further delayed final determination of allowance or abandonment.57 What may be even worse, is that such delay effectively denies applicants even an opportunity to be heard.

In addition, for the reasons discussed above, because this system also is intended to act as a protector of patent quality,58 when it fails, patent quality suffers. This results in a variety of harms to both applicants and the public.

Where It Matters

While timeliness is generally appreciated in all circumstances, it is not critical in every petition. For example, in a petition to revive an application, it is not usually critical that the petition be decided within a defined time period as there is no ticking clock with negative consequences if it runs out.59 While applicants would likely prefer to have the petition decided quickly so the matter can progress, there is no consequence to applicants other than the inherent delay if the matter is not timely decided.60

Compare this to the situation where applicants receive an Office Action and the Examiner commits a procedural error which disadvantages them and/or prevents the progression of prosecution as to at least one issue. The Office of Petitions is tasked with adjudication of just such issues.61 In these cases, the clock is ticking against applicants and the failure of the Office of Petitions to timely issue a decision effectively denies relief from the Examiner’s improper action.62

The most unjust instance is where applicants petition the completeness of an Office Action under 37 C.F.R. § 1.181.63 This petition triggers a review as to whether the Examiner has properly considered and answered the most recent response.64 Here, applicants are alleging that the Examiner has failed to advance prosecution as to at least one issue which was argued by applicants in their most recent response.65 Consider the following example. Applicants respond to a rejection under 35 U.S.C. § 103 with evidence that the claims provide unexpected results over the cited prior art. In the next Office Action, the Examiner maintains the obviousness rejection but fails to even acknowledge the evidence submitted by applicants of unexpected results. Under such facts, a petition for a complete Office Action under 37 C.F.R. § 1.181 should be granted and in many cases has been.66 As such petitions must be filed within two months of the office action mail date, when timely filed,67 the USPTO has at least four months (121 days) to issue a decision before the final six-month deadline arrives.68 When the USPTO fails to do so, applicants must act to prevent the abandonment of their application and all actions available to them come with a substantial fee.69

As mentioned above, the filing of an RCE will result in petition dismissal.70 Applicants may file a notice of appeal, but this only sets a new six-month clock which can also run out from delay by the Office of Petitions.71 Notably, the data from Figure 3 shows that 16% of petitions filed have processing times of over 181 days. Therefore, the filing of a notice of appeal does not guarantee an applicant that their petition will ever receive a decision.

Furthermore, even if the petition is ultimately granted, applicants are not allowed to recover their fees for the notice of appeal.72 The USPTO’s position on this issue is strange. Their position is that a notice of appeal “was owed at the time it was paid” and “was necessary to prevent the application from going abandoned”.73 A request for refunding the notice of appeal fees cannot be approved because under these circumstances responding to a final rejection with a notice of appeal “is not a mistake within the meaning of the statutes and regulations.”74 However, seemingly in contradiction, the Office refunded extension of time fees under the same set of facts. The Office reasoned that because the Office Action was withdrawn, the extension of time fees must be refunded because they were considered to have been paid by mistake.75 However, just like the notice of appeal fees, at the time they were paid, they were necessary to prevent the application from going abandoned. They only became retroactively unnecessary after the petition decision withdrew the original Office Action and resent the Office Action date.76

The difference in treatment between extension of time fees and the notice of appeal fee appears to be based on the filing of a notice of appeal having a separate legitimate purpose, which is to move the application to appeal and the special circumstances of this individual case.77 In a more typical case, since the result of granting the petition is that the final Office Action is withdrawn,78 there would normally be no Office Action in the record which can be appealed. Consequently, the notice of appeal would not function to move the application to appeal. Instead, the result of the petition decision is to return the case to the Examiner to prepare a new complete Office Action.79 In such a case, the separate treatment of extensions of time versus notice of appeal fees would not be logically sound. However, no instance of this occurring could be found.

The above example illustrates that the delay of the Office of Petitions leaves applicants in a position where, even in the best case scenario, they are punished with fees.80 That is, even when applicants follow all proper procedures, they are being charged fees for admitted USPTO procedural failures which are entirely out of their control. Again, although the record ultimately reflects that Office Action was improper and withdrawn from the record, applicants can still suffer monetarily from the ghost of the improper Office Action.

All these issues can be avoided if the petition is timely processed. If the USPTO is incapable of processing the petitions it receives in a timely manner, then the harm could be reduced by prioritizing petitions where a clock is ticking for the abandonment of the application.

What Happens When The Petitions Office Gets It Wrong

Applicants have the right to request review of a petition decision.81 In addition to the petition processing delay issues discussed in Part VIII,82 such delay effectively denies applicants their right to a petition decision review or correction of a petition decision which is in error.

As previously discussed, in one third of cases, petitioning delays effectively denies applicants the ability to be heard and penalizes them with unjust fees. This issue is compounded in instances where the petition decision is in error because applicants’ remedy is to file a reconsideration request in a Renewed Petition under 37 C.F.R. § 1.181 which introduces even more delay.83 Furthermore, as noted on the USPTO’s Petitions website, “[a] petition to expedite will not be considered for a petition requesting supervisory review or a petition requesting reconsideration of a petition decision.”84

Therefore, for an applicant to remedy a situation where the petition decision is in error, they have to be both fortunate enough to have their original petition processed in a reasonable amount of time and then go back into the petition docket system hoping their Renewed Petition under 37 C.F.R. § 1.181 is processed before the now even shorter clock runs out with no ability to expedite the decision.85 One might reasonably ask why it is that one of the only instances where an applicant’s ability to expedite a petition decision is curtailed when they are requesting reconsideration of a petition decision—a circumstance where time is almost certainly going to be of the essence. For an applicant to receive their deserved remedy in this situation requires quite a bit of luck.

This system is effectively one where the petition decision maker has little to no effective oversight. That is, the petition decision maker has little cause for concern that their decisions will ever be overturned or that their errors will ever be made of record. As discussed in Part II, when increased oversight is given to Examiners, their quality increases.86 There is no reason to think that this same phenomenon would not apply to petition decision makers where a lack of oversight results in a decrease in the quality of their decisions.

A cynical person could take the position that processing delay dismissal is a feature, not a bug, of the petitions system. Processing delay dismissals effectively shield Examiners from their errors and prevent even the possibility for the petition decision maker to make an error of their own. The USPTO is consequently rewarded with additional applicant fees which they would not have otherwise received.87

The First Amendment

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, while famous for its protection of free speech, also guarantees the right of citizens “to petition [their] Government for a redress of grievances.”88 While the USPTO is providing a method for applicants to petition for redress of grievances,89 if the system is denying redress without substantively considering applicants’ requests, even in instances where applicants have abided by every procedural rule set in place by the USPTO itself, does a constitutional issue arise?

While interesting to contemplate, the answer is likely not. Applicants may appeal the USPTO in federal court to address such procedural failings.90 However, applicants are very unlikely to use this remedy to address the issues above as the costs associated with it are great. Notably, applicants bear the burden of paying all expenses of such a civil proceeding.91 It is therefore economically irrational for applicants to pursue civil action in any reasonably imaginable circumstance.

From a practical standpoint, many applicants are in fact being denied their petition right. While pathways for remedy theoretically exist, the cure is worse (more expensive) than the disease.

What Are Applicants To Do?

Applicants should take care to only petition procedural and not substantive issues. Petitioners should explain the facts and specific Examiner error that was committed in clear, succinct language. This is especially important because there will likely be no time for rehearing should the petition decision maker misunderstand the petition request and improperly dismiss or deny it.92

The data shows that applicants are not petitioning incomplete Office Actions at an optimal rate.93 Properly filed petitions have a high grant rate94 and often save applicants substantial money in fees.95 Such petitions also serve to compact prosecution more quickly by advancing the contentious issues of patentability to permit an efficient determination of allowance or abandonment.96

The best hypothesis this Article can make for this apparent underutilization is a lack of applicant awareness.97 However, workflow could also be responsible for at least some of the underutilization. That is, it is common in the industry for clients and attorneys to wait until the three-month due date to prepare a response.98 Therefore, by the time a petitionable Office Action is identified it is too late to file the petition.99 Lastly, given the issues with petition decision delay, it could be the case that applicants have simply lost faith in the system to such an extent that they are choosing to avoid using it.

Hopefully, this Article provides awareness of the petition remedy and motivates attorneys to identify petitionable Office Actions earlier. The USPTO could also further its own goal of compact prosecution by publicizing and encouraging petitionable remedies to applicants and patent prosecutors registered to practice before it.

However, where the USPTO can most improve is in reducing its petition processing time. This will become especially important if applicants begin to petition incomplete Office Actions at a more optimal rate. It is foreseeable that improved applicant behavior, i.e., more optimal petition filing rates, could exacerbate the USPTO’s inability to timely process petitions by simply increasing the volume of petitions the USPTO needs to process. The optimistic viewpoint is that increased petition filing would draw attention to the issue and provoke the USPTO into better handling the timeliness of its petition decisions.100

Conclusion

Despite the clear benefits to the public and applicants for patents, efficient compact prosecution unfortunately does not appear to be the default setting. The USPTO and patent prosecutors must work together to bring it about. The USPTO can do its part by further emphasizing patent quality and timely issuing petition decisions. Prosecutors are encouraged to adapt their best practices to include early identification of Office Action incompleteness and utilizing petitions to correct these instances. While this requires increased effort from both parties, the result is a proverbial win-win increasing prosecution efficiency and quality while saving applicants time and money.

Footnotes

Footnotes

-

An applicant’s first request for continued examination (“RCE”) fee is $1,360 while the second is $2,000. RCE’s also can significantly delay the time between office actions. See USPTO Fee Schedule, USPTO, https://www.uspto.gov/learning-and-resources/fees-and-payment/uspto-feeschedule [https://perma.cc/9BKG-XMRQ]. ↩

-

A possible exception being applicants in the pharmaceutical industry where the end of patent term is the most valuable and a more highly valued strategic concern. See, e.g., Jan Berger et al., How Drug Life-Cycle Management Patent Strategies May Impact Formulary Management, AJMC (Jan. 20, 2017), https://www.ajmc.com/view/a636-article [https://perma.cc/A4H4-NF77]. ↩

-

See Manual of Patent Examining Procedure § 2103(I) (9th ed. Rev. 7, Feb. 2023) (laying out the “principles of compact prosecution”) [hereinafter MPEP]. ↩

-

See id. ↩

-

See id.; see also id. § 707.07(f). ↩

-

See id. § 2103(I) (outlining the examiners’ required review for applicants’ compliance with statutory requirements). ↩

-

See generally Sue A. Purvis, What You Need to Know About the USPTO, USPTO, https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/about/offices/ous/About_USPTO_2 0130708.pdf [https://perma.cc/3TNZ-EG6M] (describing patent prosecution as a “cooperative” rather than “adversarial” investigation between an examiner and applicant to “ensure an Applicant receives a patent only for that which they are entitled to in accordance with Patent laws”). ↩

-

The GS payscale is “used to determine the salaries of most civilian government employees.” For more information on GS-14, see G-14 Pay Scale - General Schedule 2022, FEDERALPAY.ORG, https://www.federalpay.org/gs/2022/GS-14 [https://perma.cc/2D6B-GZKD]; see also Signatory Authority, PAT. OFF. PRO. ASS’N, http://www.popa.org/about/advocacy/signatory-authority-1/#:~:text=Signatory%20Authority%20for%20Utility%20Examiners&text=The %20PSA%20program%20lasts%2013,hours%20during%20the%20trial%20period [https://perma.cc/K8XW-DE5J]. ↩

-

See Signatory Authority, supra note 8 (linking to a letter from Andrew Faile, Deputy Commissioner for Patents, which outlines the four steps of the Signatory Authority Program, each step of which lasts for approximately six months). ↩

-

See Eric D. Blatt & Lian Huang, Do Heightened Quality Incentives Improve the Quality of Patentability Decisions?: An Analysis of Trend Divergences During the Signatory Authority Review Program, 46 AIPLA Q.J. 161, 188 (2018). ↩

-

See id. at 194 ↩

-

See MPEP, supra note 3, § 1204 (“An applicant for a patent, any of whose claims has been twice rejected, may appeal from the decision of the primary examiner to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board, having once paid the fee for such appeal.”); see generally id. § 1216 (stipulating the judicial review rights of an applicant dissatisfied with a final decision of the Patent Trial and Appeals Board). ↩

-

See Blatt & Huang, supra note 10, at 188 (charting the decrease in allowances granted during promotion periods where examiners are incentivized to produce better work). ↩

-

See Patent Trial & Appeal Board (PTAB) Dashboards March 2023, USPTO, https://www.uspto.gov/dashboard/ptab/ [https://perma.cc/LGU7-7GSD]; see also USPTO fee schedule, supra note 1; Timing of an Appeal - Ex parte appeals FAQ, USPTO (Sept. 21, 2020), https://www.uspto.gov/patents/ptab/trials/exparte-appeals-faq [https://perma.cc/W3HR-6HLR]. ↩

-

See Patent Examiner Count System, USPTO, https://www.uspto.gov/patent/initiatives/patent-examiner-count-system [https://perma.cc/GG33-VQAR] (explaining that “the new count system provides incentives to examiners to conduct early interviews with applicants in the hope that RCE filings will become less necessary in many cases”). ↩

-

See Naira Rezende Simmons, Putting Yourself in the Shoes of a Patent Examiner: Overview of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) Patent Examiner Production (Count) System, 17 J. MARSHALL REV. INTELL. PROP. L. 32, 37 (2017). ↩

-

See Awards, PAT. OFF. PRO. ASS’N, http://www.popa.org/about/advocacy/awards/ [https://perma.cc/83U5-42DY]. ↩

-

See id. ↩

-

See Quality Metrics, USPTO, https://www.uspto.gov/patents/quality-metrics [https://perma.cc/7SZR-5TD2]. ↩

-

See id. ↩

-

Compare id. (approximately 12,000 cases reviewed per year) with Erin Duffin, Number of Patent Application Filings in the United States from FY 2000 to FY 2021, STATISTA (Mar. 29, 2023), https://www.statista.com/statistics/256554/number-of-patent-applicationfilings-in-theus/#:~:text=Number%20of%20patent%20application%20filings%20in%20the% 20U.S.%20FY%202000%2DFY%202021&text=In%20the%20fiscal%20year%20o f,653%2C311%20patent%20applications%20were%20filed [https://perma.cc/WEP2-WUYA] (stating the USPTO received 650,654 patent applications in 2021). ↩

-

For some evidence that this occurs in at least outlier allowance examiners, see Shine Sean Tu, Bigger and Better Patent Examiner Statistics, 59 IDEA 309, 322 (2018) [hereinafter Tu, Bigger and Better Patent Examiner Statistics] (highlighting the conditions of primary patent examiners—a larger docket of already-allowed patents and constraints on time to review applications— which leads to greater allowance rates). ↩

-

See id.; see also Quality Metrics, supra note 19. ↩

-

Communication From Author to USPTO Group Director (on file with author). ↩

-

See id. ↩

-

See Tu, Bigger and Better Patent Examiner Statistics, supra note 22, at 320 (emphasizing that “since there are no legal rights given to an applicant after a rejection, rejections do not receive the same scrutiny as allowances”). ↩

-

For example, production and docket management. ↩

-

See discussion supra Part II. ↩

-

See 37 C.F.R. § 1.181(a)(1) (2021) (allowing petitions to the Director of the USPTO). ↩

-

See id. There are no fees for such a petition. ↩

-

Based on author's experience. ↩

-

See MPEP, supra note 3, § 707.07(f); see also id. § 2145 (“Office personnel should consider all rebuttal arguments and evidence presented by applicants.”). ↩

-

See id. § 707.07(f) (indicating that without further probing by an examiner, both the USPTO and an applicant are constrained to take the applicant’s unquestioned arguments at face value). ↩

-

E.g., In re Application of Ladd et al., Dec. Comm’r Pat. (Feb. 4, 2021); In re Application of Hiroaki Yamada et al., Dec. Comm’r Pat. (Aug. 30, 2022). ↩

-

See generally Patent Term Adjustment Data March 2023, USPTO, https://www.uspto.gov/dashboard/patents/patent-term-adjustment.html [https://perma.cc/58RS-XWP6]. An in-depth discussion of PTA is beyond the scope of this Article. ↩

-

See Shine Tu, Patent Examiners and Litigation Outcomes, 17 STAN. TECH. L. REV. 507, 510 (2014) (rejecting certain “intuitive hypotheses” and arguing that “patent examiners who issue the most patents actually issue relatively fewer litigated patents,” which implies that better quality examination results both in more efficient prosecution and more litigation-proof patents). ↩

-

See Shine Tu, Invalidated Patents and Associated Patent Examiners, 18 VAND. J. ENT. & TECH. L. 135, 138 (2015) [hereinafter Tu, Invalidated Patents and Associated Patent Examiners] (“Errors that could be prevented at the USPTO would save litigants and consumers millions of dollars.”); see also AIPLA, 2017 REPORT OF THE ECONOMIC SURVEY 41 (2017) (attesting that in 2017 the median litigation cost for a patent infringement suit was about $0.5–3 million. depending on the amount at risk). ↩

-

See generally Tu, Invalidated Patents and Associated Patent Examiners, supra note 37. ↩

-

See Petition Search & Analytics Platform, PETITION.AI, https://petition.ai/ [https://perma.cc/3YVQ-TFTF]. Petition.AI database was searched for petition requests for relief and associated petition decisions on the basis of an incomplete office action (last searched December 7, 2022). ↩

-

A normal distribution is otherwise known as a bell curve or Gaussian distribution. See Normal Distribution, ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, INC. (May 15, 2023), https://www.britannica.com/topic/normal-distribution [https://perma.cc/EC2L-PPBN] (“Its familiar bell-shaped curve is ubiquitous in statistical reports, from survey analysis and quality control to resource allocation.”). ↩

-

The data was hand counted by the author after reviewing the petitions in the Petition.AI database. ↩

-

In all the petition decisions over this time period, there were only a few instances of denial. See PETITION.AI, supra note 39. There were 36 total grants, 26 total dismissals, and 3 total denials. ↩

-

See id. ↩

-

The data was hand counted by the author after reviewing the petitions in the Petition.AI database. ↩

-

See id. ↩

-

See generally 37 C.F.R. § 1.181 (2021) (stipulating what is petitionable to the Director of the USPTO). See also MPEP, supra note 3, § 1002 (“Petitions on appealable matters ordinarily are not entertained.”). ↩

-

See 37 C.F.R. § 1.181(f) (2021). ↩

-

See MPEP, supra note 3, § 711. ↩

-

See, e.g., In re Application of Adlem et al., Dec. Comm'r Pat. (July 27, 2018) (holding the filing of an RCE rendered the petition moot). ↩

-

See Michael Spector & Julie Burke, Petition Pendency's Impact on Grant Rates, PETITION.AI (Nov. 10, 2021), https://petition.ai/blog/petition-pendencys-impact-on-grant-rates [https://perma.cc/VMF9-JLDU] [hereinafter Spector & Burke, Petition Pendency's Impact on Grant Rates]. ↩

-

See Michael Spector & Julie Burke, Petitions Filed After Final Dismissed as Moot: USPTO Runs Down the Clock (Part IV), PETITION.AI (Nov. 18, 2020), https://petition.ai/blog/petitions-filed-final-dismissed-moot-uspto-runs-clock-part-iv [https://perma.cc/MH9J-Z9C3] [hereinafter Spector & Burke, Petitions Filed After Final Dismissed as Moot]. ↩

-

See, e.g., In re Application of Adlem et al., supra note 49. ↩

-

See id. ↩

-

Calculated by removing the 0–30 day slice of the pie to remove automatically granted petitions. See Spector & Burke, Petition Pendency's Impact on Grant Rate, supra note 50. ↩

-

Quote attributed to William Gladstone. ↩

-

See Spector & Burke, Petition Pendency’s Impact on Grant Rate, supra note 50 (highlighting that “the faster the USPTO mails the petition decision, the higher the grant rate[; w]ith each month the petition had yet to be decided, the grant rate declined 4-5 percentage points”). ↩

-

For example, extension of time fees. See Spector & Burke, Petitions Filed After Final Dismissed as Moot, supra note 51 (noting the seemingly arbitrary discrepancies in promptness and accuracy of petition information enter into the Public Patent Application Information Retrieval (PAIR) Image File Wrapper (IFW)). ↩

-

See supra Part V; see also Tu, Invalidated Patents and Associated Patent Examiners, supra note 37, at 139 (noting several programs the USPTO has implemented to assure patent quality). ↩

-

See MPEP, supra note 3, § 711 and the various discussed requirements of a petition to revive depending on the specific facts of the particular application, supra Part VII. ↩

-

See MPEP, supra note 3, § 711. ↩

-

See 37 C.F.R. § 1.181 (2021). See generally MPEP, supra note 3, § 707.07(f). ↩

-

There is a six-month deadline for a response to an Office Action, with associated fees required within the last 3 months. See MPEP, supra note 3, § 710 (9th ed. Rev. 7, Feb. 2023); see also 37 CFR 1.136 (2023) (providing procedures for extension of time). ↩

-

See infra Part IX. See generally 37 C.F.R. § 1.181. ↩

-

See 37 C.F.R. § 1.181 (2021). ↩

-

Grounds for this petition are supported by, for example, MPEP, supra note 3, § 707.07(f) (“Where the applicant traverses any rejection, the examiner should, if they repeat the rejection, take note of the applicant’s argument and answer the substance of it.”); see also id. § 2145 (“Office personnel should consider all rebuttal arguments and evidence presented by applicants.”). ↩

-

See In re Application of Ladd et al., supra note 34 (deciding a new office action should be issued following an examiner's failure to consider evidence of unexpected results); see also In re Application of Hiroaki Yamada et al., supra note 34 (holding likewise). ↩

-

See 37 C.F.R. § 1.181(f) (2021). ↩

-

See MPEP, supra note 3, § 710 (stating that failing to prosecute an application within six months of any action therein shall result in abandonment). ↩

-

See USPTO Fee Schedule,supra note 1 (explaining that the fee for an initial RCE is $1,360 while the second is $2,000, and that the fee for a Notice of Appeal is $840); see also MPEP, supra note 3, § 711. ↩

-

See In re Application of Adlem et al., supra note 49. ↩

-

See MPEP, supra note 3, § 710. ↩

-

See, e.g., In re Application of Kawahara et al., Dec. Comm'r Pat. (Sept. 13, 2016), US 12/528,487 (holding that no refund would be issued for an appeal fee because “[t]he fee for the Notice of Appeal was owed at the time it was paid… was necessary to prevent the application from going abandoned”). ↩

-

See id. ↩

-

See id. ↩

-

See id. ↩

-

See id. ↩

-

See MPEP, supra note 3, § 1204. Because the notice of appeal was filed (July 5, 2016) after the time when a complete Office Action was determined to have been issued (June 20, 2016), there was an Office Action of record which could be appealed and thus the Notice of Appeal functioned to appeal this Office Action. ↩

-

See, e.g., Petition Decision of February 4, 2021 in US 15/868,357 and August 30, 2022 in US 16/494,113. ↩

-

See id. ↩

-

E.g., extensions of time, RCE, Notice of Appeal, etc. See also Petition Decision of February 4, 2021 in US 15/868,357 and August 30, 2022 in US 16/494,113. ↩

-

See Petitions, USPTO, https://www.uspto.gov/patents/apply/petitions [https://perma.cc/QZD9-382K] (answering frequently asked questions). ↩

-

See supra Part VIII. ↩

-

See Petitions, supra note 81 (answering frequently asked questions). ↩

-

See id. ↩

-

See 37 C.F.R. § 1.181 (2021); see also MPEP, supra note 3, § 1002 (referencing the two-month deadline from the mailing date of the action or notice from which relief is requested). ↩

-

See supra Part II. ↩

-

See generally USPTO Fee Schedule,supra note 1. ↩

-

See U.S. CONST. amend. I. ↩

-

See supra Part IV. ↩

-

See 35 U.S.C. § 141 (noting that an applicant that is dissatisfied by the final decision in an appeal to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board can appeal the Board's decision to the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit); see also 35 U.S.C. § 144 (discussing how the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit can review decisions on record from the PTO and then issue their decisions to the Director who then enters that decision in the record for the PTO) ↩

-

See 35 U.S.C. § 145. ↩

-

It is suggested that applicants begin their petition by noting that the petition is not seeking review of substantive issues. This can signal to the petition decision maker that applicants understand what subject matter is appropriate for petition review and increase the chances that their petition request is not misunderstood as requesting review of a substantive issue. ↩

-

See supra Part VI. ↩

-

See id. ↩

-

If a petition is granted the Office Action is withdrawn, ergo no fees. ↩

-

See supra Parts II, V. ↩

-

In the personal experience of the author, most attorneys express surprise when told that such petitions even exist. ↩

-

Based on the author’s personal experience. ↩

-

Petition must be filed before the 2-month deadline. See MPEP, supra note 3, § 1002. ↩

-

A virtuous circle effect where applicants’ increased filings provoke better handling which provokes even more filings. ↩